“We are all writing towards and against dominant histories, whether consciously or not. “

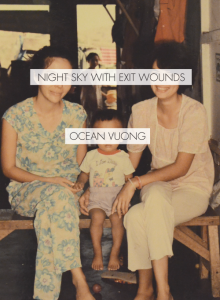

Ocean Vuong is the author of The New York Times bestselling novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, out from Penguin Press (2019) and forthcoming in 30 languages. A recipient of a 2019 MacArthur “Genius” Grant, he is also the author of the critically acclaimed poetry collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds, a New York Times Top 10 Book of 2016, winner of the T.S. Eliot Prize, the Whiting Award, the Thom Gunn Award, and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. A Ruth Lilly fellow from the Poetry Foundation, his honors include fellowships from the Lannan Foundation, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, The Elizabeth George Foundation, The Academy of American Poets, and the Pushcart Prize. Born in Saigon, Vietnam and raised in Hartford, Connecticut in a working class family of nail salon and factory laborers, he was educated at nearby Manchester Community College before transferring to Pace University to study International Marketing. Without completing his first term, he dropped out of Business school and enrolled at Brooklyn College, where he graduated with a BA in Nineteenth Century American Literature. He subsequently received his MFA in Poetry from NYU. He currently lives in Northampton, Massachusetts where he serves as an Associate Professor in the MFA Program for Poets and Writers at UMass-Amherst.

![]() Why use poetry to explore history? How does poetry make us alert to history?

Why use poetry to explore history? How does poetry make us alert to history?

I think that, unlike textbooks and newspaper articles, poetry offers us a more complex enactment of human emotion— especially in the context of a historical moment. It is liberated from the agenda of “pure documentation” in the way news reporting might be subject to. Instead, poetry allows an alternative exploration, one that is as complex and layered in opinions and feelings as there are perceivers, an exploration unbounded by the anxiety for answers, but rather, the ambition to ask more difficult and provocative questions. I think this is one of poetry’s values: it’s malleability, which invites, even beckons us, to be active participants in how history is digested and recorded. When we have the power and permission to explore history on our own terms, with our own language, we become true inheritors of the world we live in.

![]() Do you see as one of the goals of your poetry to teach your readers something about history? How can a poem teach us about an historical event differently than an article or textbook?

Do you see as one of the goals of your poetry to teach your readers something about history? How can a poem teach us about an historical event differently than an article or textbook?

No, at least that is not my goal. Although I suppose someone might learn something anyway—as I often do myself when reading other poets. But I think an anxiety to “teach” or “present” an idea can hinder a poem’s possibility. I want to make a poem the way people make rooms. You can walk into it and just look around, what you take or learn from it is up to you. Maybe you just walk right through it, to the next room. But that’s the beauty of the art, the reader is as much an active participant in its perception as she is of her own life.

![]() What is the role of research in your writing process? What responsibilities do you feel to “historical fact”?

What is the role of research in your writing process? What responsibilities do you feel to “historical fact”?

Come to think of it, I never really do research for my poems. Rather, the pieces are often written from knowledge I’ve internalized through historical contexts that I have encountered, through various means, and have digested or have fermented within me. I think I trust the impulse to write about history more when I have carried the particular event or idea inside me for some time, allowing it to grow and shift within my psyche. In the case of “Aubade With Burning City,” I knew the story of “White Christmas” being played during the fall of Saigon from my grandmother’s re-telling of her experience. I always listened to her while imagining the tropical city of my birth being covered with snow in the midst of that chaos. The scene, part fiction of my imagination and part truth, played itself out again and again in my head long before I decided to write poems. What little research I did was at the end, after the poem had already been finished, to fact-check and get dates and names right. Of course, the degree of research always depends on the poem and its relation to its history.

![]() On a practical note, what kinds of extra-poetic apparatus—notes, footnotes, epigraphs, references, etc.—do you find useful as a reader and writer of poetry that engages history?

On a practical note, what kinds of extra-poetic apparatus—notes, footnotes, epigraphs, references, etc.—do you find useful as a reader and writer of poetry that engages history?

I think they are only helpful if they assist in setting the framework of the poem. In other words, you want to allow the poem to get into its explorations as quickly as possible, without spending too much time/words explaining itself. In this way, extra-poetic apparatus can be helpful; it delivers you into the center of the context, so that the poem can do its necessary, immediate work. Still, I think it should not compete with the poem, or draw attention away from the work.

![]() Your poems are very beautiful and yet often record violent experience. What do poets and readers need to think about when violence is made beautiful by the language of a poem? Is this a tension you feel in your writing? Is it a tension to be reconciled?

Your poems are very beautiful and yet often record violent experience. What do poets and readers need to think about when violence is made beautiful by the language of a poem? Is this a tension you feel in your writing? Is it a tension to be reconciled?

I feel that when violence is made beautiful merely as a feat of novel transformation, art stagnates. Poetry offers us an opportunity to redefine words, including “beauty.” As such, in my own poems, if the only result were that “violence is made beautiful by language,” then I would have failed (which might be more often than I’d like). The perception of beauty as a fabrication of violence might, indeed, still occur—but only as a result of another goal, which is perhaps the recording and enacting of desperation. As far as I can remember, I have been attracted to the idea of desperation, the will to live under impossible trauma and ruptures, the resilience to insist on one’s own life, often when no one else is willing to do so. It is not that violence can be beautiful, (although sometimes true, that does not interest me as much) but rather, that life can be beautiful despite of violence, and to record that moment of resilience is, to me, one way of honoring survival. For example, one of my friends told me about this miraculous sea sponge that, if you were to cut it up into pieces, then toss it into a tub of water, it would reattach itself with in a few hours, seamlessly. That’s beautiful to me, perhaps even more so than beauty itself. I hope my poems can do that.

![]() How can a poem be a space where public and personal histories can intersect? Is your work building toward any resistance or challenge to dominant histories and their traditional treatments of certain topics, people, and places?

How can a poem be a space where public and personal histories can intersect? Is your work building toward any resistance or challenge to dominant histories and their traditional treatments of certain topics, people, and places?

I think there’s really no avoiding it for me—but maybe this can also apply to anyone. We are all writing towards and against dominant histories, whether consciously or not. This is because we are all the sum total of our times, our era. Just like the world’s actions affect the air we breathe, the food we eat, the water we drink, I think to be a poet is to be affected by the planet we live on—replete with its histories. Even if we tell ourselves, “I’m sick of this world. I shall write about Mars,” planet Earth, along with her joys and terrors, will find her way through us, and out of us, and into our work. As we cannot take off our identities the way one takes off a mask, we cannot divest ourselves of our global historic past—because, more than anything, it is human. And to be human is to remember, despite of it.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

I used to write in my journal. Just prose meditations and daydreams, really. Nothing serious. But the jocks in my high school would make fun of me for it. They would take my notebooks and throw them in the garbage pails at lunch and pour milk on them. Then, one day, in math class, one of the jocks, a basketball player, approached me after the bell rang. He told me his grandfather had just died and his family wanted him to write a eulogy at the funeral. He asked me to write it for him. He was suddenly very shy and very soft spoken. And I saw then that we were not very far away, not very different. So I wrote it for him. Something clichéd about the light of a candle never truly diminishing, even long after it burns out, as the ashes that rise become the parts of the air we breathe and live through. I handed it to him in an envelope. He never said anything about it afterwards. I don’t even know if he used it for the funeral. But he and his friends stopped pouring milk on my notebooks.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

I think it can. We use the word talent a lot but I find it to be a lazy, dismissive word. What is really at work is permission to self-investigate and explore one’s obsessions. Creative Writing is taught not by showing one how to be creative per se, but by allowing someone to enact the rich, startling, idiosyncratic mind they already possess. In this way, I think creativity is about growth and self-expansion. It is not something you must obtain, but nurture. You already have it. And teachers are often the best nurturers. I certainly would not be able to write the way I do now without some crucial and kind teachers in my life.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

Making by Tim Ingold

The Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

The Breakbeat Poets anthology

The Book of Martyrdom and Artifice: early journals of Allen Ginsberg

Madness, Rack, and Honey by Mary Ruefle

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

It’s okay to write to the most terrified versions of yourselves.

What are you working on now?

Making dinner for my boyfriend.

Can you give us a poetry prompt for our students?

Write a poem with the anaphora “I remember…” (after Joe Brainard) but in the voice of your mother. You can remember what she told you of her life–or you can make it up. Try to write at least 30 lines. Try to include details of a specific city, a piece of clothing, the light in a room, the time of day, the sounds the weather made. Pick an image that is important to you in the poem that will reappear again and again. With each reoccurrence, try to make it change a little bit, add or take away from it until it transforms into something else. For example: snow slowly falling into shredded paper. Don’t be afraid to be strange. Don’t be afraid to be wrong. Finally, how does your mother remember you? How would you describe yourself through her eyes?