“I simply want to make the claim that the mind is formed by the shape of the land, by the sheer geography of the mind’s physical location. And the shape of the mind, under the influence of the land, will yield a particular kind of poem with a particular kind of expression.”

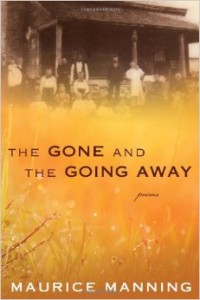

Maurice Manning is the author of five books of poetry, including The Gone and the Going Away (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013). His fourth book, The Common Man (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010), was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2011. His first book, Lawrence Booth’s Book of Visions (Yale University Press, 2001), was selected by W.S. Merwin for the Yale Series of Younger Poets. Manning’s other books include A Companion for Owls (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004) and Bucolics (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007). He has held fellowships at The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown and The Hawthornden International Retreat for Writers in Scotland. In 2009, Manning was awarded the Hanes Poetry Prize by The Fellowship of Southern Writers. In 2011, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 2012 he received the Lee Smith Award from Lincoln Memorial University. Manning teaches at Transylvania University and in the MFA program for writers at Warren Wilson College. He lives in Kentucky.

![]() Many writers have talked about “a sense of place” in their work. What, to you, is your “sense of place” as a poet? How can poetry be a space for imagining and reimagining places in our lives? Why do it?

Many writers have talked about “a sense of place” in their work. What, to you, is your “sense of place” as a poet? How can poetry be a space for imagining and reimagining places in our lives? Why do it?

In Kentucky, we say the original land of a family is the “homeplace.” The homeplace of my mother’s family is still intact and is still land owned by descendants of the original settlers. Even the actual home made of log and stone still exists. That’s going back more than 200 years. It is a similar story for my father’s side of the family—I have relatives still living in the ancestral place. What was most formative to me was knowing my older relatives who had a long and passed-down relationship to the same place. So, I have a geographical and historical sense of place that is sort of a hundred-mile loop and more than two hundred years old. Part of my effort as a poet—though I couldn’t have said this at the beginning—has been to populate that loop with characters, some imagined and some real, and find a way to demonstrate through that particular geography and history, how that loop has influenced and shaped a poetic mind. My inheritance is not material; rather, it has been cultural, what scholars now say is Appalachian. In my family we simply say we’re mountain people, meaning the southern Appalachian and Cumberland mountains. I could go on at length, but to put it concisely, my effort as a poet has been to learn that particular cultural tradition and to make the claim that beauty and spiritual dignity are inherent to such a tradition, and even whim and wildness are part of it.

Why do it? Because it is my inheritance and the root of my own being.

![]() What do you hope to capture about a place—whether specifics of a landscape or, more generally, a sensibility—when writing a poem that invokes or references a landscape?

What do you hope to capture about a place—whether specifics of a landscape or, more generally, a sensibility—when writing a poem that invokes or references a landscape?

My local and my ancestral geography is rugged—up and down hills, with lots of dark hollows. I’m not especially interested in psychology, but I think the shape and the character of the land—of the natural place—influences the shape and the character of the mind that lives in the presence of that place. For example, the farm where I live has a hollow. Because of the geography, that part of our land is in shadow much of the day; it is in deep darkness at night. That’s a sharp contrast to a couple of fields we have that get lots of sun during the day and are open to the wide sky at night. In that case, it is the sharp contrast that interests me—how something dark can be side by side with something light, and how the boundary between the two is always blurry. Hopkins saw this for sure; Wordsworth and Coleridge observed it earlier, and James Still and Robert Penn Warren observed it later, among others. I simply want to make the claim that the mind is formed by the shape of the land, by the sheer geography of the mind’s physical location. And the shape of the mind, under the influence of the land, will yield a particular kind of poem with a particular kind of expression.

![]() Is there any way you think your work speaks to a particular audience, among others, because of a sense of place it evokes?

Is there any way you think your work speaks to a particular audience, among others, because of a sense of place it evokes?

I hope that is the case. I have readers from my region in mind when I write, but I don’t want anything I do to seem exclusive. We all live in a specific place. What matters is if we notice, if we pay attention and learn to value our place. Too many of us take our place for granted, and too many of us think our place is of no special value.

![]() Is your physical environment important to you as a writer in the act of writing? Are there certain places—a desk in your bedroom, a local coffee shop, a library—where you feel most productive, most artistically “at home”?

Is your physical environment important to you as a writer in the act of writing? Are there certain places—a desk in your bedroom, a local coffee shop, a library—where you feel most productive, most artistically “at home”?

My physical environment is essential. Usually when I’m contemplating a poem I walk through our woods and see what happens to fall into my ear. I like to begin outside and see how that influences the inside. Our farm has increasingly become a kind of mythic origin for whatever I have to say in a poem. From there, I sometimes stretch that to include something cultural or historical to our general region, hoping that may be accessible to a general reader. Or not—sometimes, I like to take something local and just put it out there, as a surprise or a point of thought for anyone who may be interested. I like to keep it local, but also keep it open, as much as that is possible.

![]() Your poems indicate a sense of place to us as much as through tone and diction as through narrative and image. How do you capture the particular language of a place in a poem?

Your poems indicate a sense of place to us as much as through tone and diction as through narrative and image. How do you capture the particular language of a place in a poem?

I listen. All of my poems begin with the ear, with the sound of something that appeals to the ear. Sometimes the poem is based on a particular word, sometimes it’s based on the natural rhythm of a phrase, sometimes it’s a combination and sometimes it’s a sound-image, based solely on some physical fact of the geography or ecology. The screetch and skritch of bugs in the trees in summer is a constant. The cold silence from those same trees in winter is also a constant. Sometimes there’s a word that comes to mind, sometimes there isn’t a word. I most prefer the in between—the not quite silence from the world, and the not quite distinguishable sound.

![]() Are you ever worried about a reader not understanding something specific in an unfamiliar vernacular?

Are you ever worried about a reader not understanding something specific in an unfamiliar vernacular?

No. I like to challenge the reader, because I like to challenge myself to engage the ineffable. I want to give him or her something to ponder, something he or she may not quite know. That’s my own interest in all things poetic, and it seems appropriate to want to share the uncertainty with a reader. That way we have a shared space of listening and thinking, and the result of all that thinking is, hopefully, always unresolved.

Can you describe the “Boss” character in your Bucolics poems?

In some ways, the character of “Boss” is still forming. I don’t ever want that character to become a fixed identity. I want it to be open and expansive. Yes, on one hand “Boss” is a God character in some traditional sense, but I always want to think of God as beyond our comprehension. We have a few possible claims, but then those claims fall short and don’t adequately define “Boss.” That is how I encounter God, as a presence and as a confounding mystery at once.

![]() Do you feel your geographic location—your proximity or distance from the places you write about—affects your writing about those places? A few years ago, you moved back to Kentucky after teaching at Indiana University. How have these changes—in your landscape and in your teaching—shaped the course of your recent writing?

Do you feel your geographic location—your proximity or distance from the places you write about—affects your writing about those places? A few years ago, you moved back to Kentucky after teaching at Indiana University. How have these changes—in your landscape and in your teaching—shaped the course of your recent writing?

I have always held the landscape and the history of Kentucky in my mind. That has been the constant source of my poetry. I have enjoyed the experience of writing about it from a short distance, and from within the place itself, but the source has remained the same. I like to think I’ve worked along a radius, but the center-point has been consistent.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

The more I think about it, the more I realize I came to poetry young. It was in the air, in the language I grew up hearing, in the stories my elders told. There was grit in the words I heard, music in the phrase, and mind and character in the tale. So much of it was ready for my ear and I was fortunate to be a good listener.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

I think technique can be taught—how to measure a line, how to render a simile, but an imaginative mind is something different. Although I firmly believe in the democracy of education, a truly imaginative mind seems to be an outright gift, or something one scrambles to find as a means of survival.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

I think this is a personal matter. We all have different books that matter to us, and different writers who inspire us. My own list of inspiring writers is always expanding and always changing. Here a few writers I have been clinging to in recent years: Robert Penn Warren, James Still, Vachel Lindsay, Robert Frost, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Allen Tate, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Hopkins, Edward Thomas, and R.S. Thomas. There are many more. I can’t have a reduced or concise reading list. Too many writers light a fire in me—D.H. Lawrence, Faulkner, Agee, Hayden, Cather, Hurston, not to mention Walker Percy and Kurt Vonnegut, and not to mention contemporary writers who are my dear friends. This is a question that has no end.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

Harry Brown, a Kentucky poet, once told me, “Your well is already full,” when I told him I was waiting to write until my “well” of experience was filled enough to have something to say. David Wojahn advised me to be careful of ending a line with a preposition. Both were right. James Still gave me some pointers—mainly that a writer is foremost a reader and a widely ranging reader. There is much more I could say. I have been lucky to have dear and salty mentors. The good quotes about writing and the work of being a writer are out there, and most of them seem to apply. I can say this with certainty: it is indeed work, work to enjoy and work to endure, and work whose value may take time before it is understood.

What are you working on now?

I’m always working on new poems, new forms, new styles of writing, hoping to keep what I’m doing fresh for me and therefore alive for my reader. And I’m always returning in my reading. Recently, I’ve returned to Herman Melville and Stephen Vincent Benet. There is no end to this, no particular pinnacle. Eudora Welty is in there, Flannery O’Connor is always present as a spirit-guide, and Dickinson, and Whitman, and Emerson and Thoreau, and Stevens and Frost. I’m an American poet in spirit, perhaps a more particular poet in practice. It’s a privilege to do what I do.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

I gave a simple assignment to some high school students this summer and was pleased with the result. Here it is: write a haiku titled “Ish.”

As you know, “ish” is a word that has suddenly appeared in the English language. I hear it used all the time in casual conversation and have been surprised how quickly it has come into widespread use. I think this is great, because it further demonstrates that English is a real mongrel language. And many things can be thought of through the lens of “ish.” Also, I like thinking about the haiku form in this context. The haiku, because it’s so compact can seem like an “ish” poem, something that’s almost but not quite a poem. Yet a really good haiku can strike us in 17 syllables and three lines as potently as any longer, more involved poem. Less is more in poetry, and the very idea of “ish” nicely conveys that.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- How would you describe the speaker of Maurice Manning’s eight “Bucolics” poems? What attributes do you learn about this speaker over the course of the poems?

- Manning speaks in his interview about the ways sounds can evoke a place. How do his poems evoke sounds? How do his poems create new sounds? From listening and learning from these poems, how would you describe the sounds of Appalachia?

- A “bucolic” is, typically, a poem that evokes the pleasant aspects of the countryside and country life. In what ways are Manning’s “Bucolics” representative of this definition? In what ways do they challenge it?

- Manning says that it is important to imagine and reimagine places in poems because they are at “the root of [his] own being.” What are your roots? How might they affect the poems you write and the choices you make as a writer?

- How does the character of “Boss” work in the “Bucolics” poems?

- In what ways do the “Bucolics” poems address the character of “Boss” as well as address us, the readers?

In-class Activities

This four-part exercise is designed to be used to foster in-class discussion, brainstorming, and writing. Students will consider which details of landscapes might be useful for writers, as well as generate some language specific to landscapes that are important to them.

Prompts

Lightbox Writing Prompt:

In his interview, Rickey Laurentiis writes, “For me, it’s important to remember that place in poetry is as much, if not more of, an imagined space as it is an “actual” description or representation of that place.” Of his “homeplace,” Maurice Manning writes, “We all live in a specific place. What matters is if we notice, if we pay attention and learn to value our place.” Think about a place that is important to you. Perhaps it is the house where you grew up, a place where you created a favorite memory, or a space of quiet contemplation.

Write a draft in which you try to imagine this place as richly as possible. Make decisions about aspects of the place you will describe, aspects you will seek to represent, and aspects that will remain, for your reader, merely imagined. Experiment with using an epigraph that designates a specific place and see how the poem is affected.

Maurice Manning’s Writing Prompt:

Write a haiku titled “Ish.”

As you know, “ish” is a word that has suddenly appeared in the English language. I hear it used all the time in casual conversation and have been surprised how quickly it has come into widespread use. I think this is great, because it further demonstrates that English is a real mongrel language. And many things can be thought of through the lens of “ish.” Also, I like thinking about the haiku form in this context. The haiku, because it’s so compact can seem like an “ish” poem, something that’s almost but not quite a poem. Yet a really good haiku can strike us in 17 syllables and three lines as potently as any longer, more involved poem. Less is more in poetry, and the very idea of “ish” nicely conveys that.

Maurice Manning Online

Buy The Gone and the Going Away by Maurice Manning

Buy The Gone and the Going Away by Maurice Manning