“In life, there is mystery. The mysteries are no more profound in medicine than in poetry. I question, and I doubt, and I think. I have been that way my entire life.”

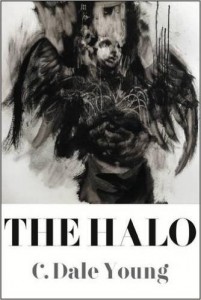

C. Dale Young is the author of four collections of poetry, including Torn (Four Way Books 2011) and The Halo, forthcoming from Four Way Books in early 2016. His linked short story collection The Affliction is due out from Four Way Books in 2018. A recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation, he practice medicine full-time and teaches in the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers. He lives in San Francisco.

![]() How do you balance the actual logistical, as well as the spiritual or emotional, work of being a poet and being a full-time medical doctor?

How do you balance the actual logistical, as well as the spiritual or emotional, work of being a poet and being a full-time medical doctor?

I am not sure I ever feel as if I balance the work of being a poet and a physician. I do wake at 5:25 AM most weekday mornings to get a few writing-related things done before I head off to the hospital. I am not usually home until early evening. By then, I am often too tired to read or write. Most of my writing, when it does happen, is on weekends, or the occasional Wednesday I have as an admin day for my Practice. Considering the fact I typically finish roughly four poems a year, one could argue there is little balance in my life between these two endeavors. Last year (2014), I only finished two poems. I have to admit though, that I also write fiction in addition to poetry, so a fairly sizable chunk of my writing time over the past seven years has been devoted to that.

My field of practice in medicine is Radiation Oncology. Oncology can be a very difficult field, filled with an unbelievable amount of emotion. I tend to reserve most of my stability and humanity for my job as an Oncologist, the job where I am face to face with people. I guess the reality is that I spend the vast majority of my time being a physician. I often need things like this interview to remind me I am a writer at all.

![]() Would you describe the process of writing the poem, “Torn”?

Would you describe the process of writing the poem, “Torn”?

When I finished my medical residency in Radiation Oncology at UCSF, I joined a practice. That first year in practice was, to say the least, overwhelming. I had to learn three new hospitals, three groups of referring physicians, three different department staffs, etc. I was also studying for my medical specialty Board exams. The only reading I did that year outside of medicine were the poems submitted to New England Review, where I was poetry editor at the time. I wrote no poems that year. I felt void of poems. I was barely treading water trying to keep up with Medicine. It was the only year in my life as a physician that totally wore me down. After I finished my Board Exams, I re-read Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s book Song. Once again, I was floored by the title poem. I decided to copy it out in longhand, convinced the process of doing that would teach me more about this poem I so loved. I wrote it out in longhand a few times. A day or so later, I wrote “Torn.”

Most of my poems come piecemeal or very slowly. “Torn” is among a small handful of my poems that arrived differently. “Torn” poured out of me. I wrote it in one sitting. I was so disturbed by it, I almost threw it away. I showed it to the poet Carol Frost, who confirmed for me it was, indeed, a poem; she told me not to throw it out.

![]() Your poem, “Proximity,” is about naming or identifying something—putting something to words so that it can be controlled or understood. How do you draw connections, in your life as a doctor, between reading and interpreting bodies and the way the speaker in “Proximity” reads and interprets his sources—not only medicine, but also the Gospel of Mark, Cher, and Augustine?

Your poem, “Proximity,” is about naming or identifying something—putting something to words so that it can be controlled or understood. How do you draw connections, in your life as a doctor, between reading and interpreting bodies and the way the speaker in “Proximity” reads and interprets his sources—not only medicine, but also the Gospel of Mark, Cher, and Augustine?

I believe all writers do this. We are wired, I believe, to look for connections. We all draw from our lives, both real and imagined. The only difference between me and most writers is I am also a physician. I tried for many years not to write about anything to do with medicine, but it becomes impossible over time to exclude something that takes up so much of your life. I love to read. I love visual art and philosophy. I don’t aim to place all of these things into poems, it is just that they are already in my mind. They end up in my poems. It is human to want to name things. It is human to want to fill in the story even when all we are presented with are a few details.

As for reading and interpreting “bodies” as a physician, I should mention I never write about a single patient of mine in a poem or story. I would feel as if I were betraying the Hippocratic Oath, betraying my patients’ confidences. By default, any patient in one of my works is actually an amalgam of various patients I have had. The power of being a physician, the responsibility, outweighs my desires as a writer.

![]() How can poetry be a space for creating understanding about the work of medicine and about the experience of being a doctor or a patient?

How can poetry be a space for creating understanding about the work of medicine and about the experience of being a doctor or a patient?

I am not entirely sure it can. Poetry allows us a chance to interact with the human imagination in all of its range and surprise. To be a good physician, one should be able to interact with human beings, people, not just their disease. So, poetry and Literature in general can be good things for doctors, but they are good things for everyone really. They allow us the chance to walk in someone else’s shoes. They show us the wide range of what it is to be human and not just what it takes to be ourselves.

![]() There’s so much we don’t know about the workings of the body, so much mystery. For you, is there a relationship between the kinds of questions you’ve asked yourself about the mysteries of the body and the questions you pursue in your own poems?

There’s so much we don’t know about the workings of the body, so much mystery. For you, is there a relationship between the kinds of questions you’ve asked yourself about the mysteries of the body and the questions you pursue in your own poems?

I have studied in the Temple of Apollo for most of adult life, Apollo being both the god of poetry and the god of healing. I am an inquisitive man. I question everything. I don’t think of medicine and poetry as binaries. They are things I do, that I study, but I don’t see them as in opposition to one another, something I believe this question holds as bias at its core. In life, there is mystery. The mysteries are no more profound in medicine than in poetry. I question, and I doubt, and I think. I have been that way my entire life.

![]() There is currently an interest in bridging the worlds of medical education and more humanistic study through reading workshops or curricula focusing on “narrative medicine.” What ways might you propose to enhance medical education using poetry, and conversely, how might poets benefit from the interpretation of bodies that is the domain of medicine?

There is currently an interest in bridging the worlds of medical education and more humanistic study through reading workshops or curricula focusing on “narrative medicine.” What ways might you propose to enhance medical education using poetry, and conversely, how might poets benefit from the interpretation of bodies that is the domain of medicine?

It may come as a surprise, but I am deeply suspicious of this trend toward “narrative medicine.” It seems hokey to me. It tries to remedy a problem rather than facing it head on at the source. “Narrative Medicine,” to me, seems to want to humanize physicians-in-training by asking them to look outside the science of the profession at the humanities, the personal elements that allow us to care of patients. But I find that to be simply using the methodology of science and medicine to “cure” the problem. I would argue that is simply treating a problem rather than preventing it. I believe the study and practice of medicine requires a knowledge of and understanding of biological science, but we have made a fetish of it. If you want more humane doctors, go after people who didn’t just study science in college. Bring in people who already understand the humanities, who already have other skills. Instead of trying to turn science-oriented people on to Literature and the humanities with one class on narrative medicine, go after people who will arrive in medical school with those skills already in place.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

I started out as a student of the visual arts. As a child I was a voracious reader, but I never imagined one could just become a writer. But painting, it seemed one could become a painter. Through serendipity, I began working at the college literary magazine wanting to work more with art and the publication of art. But everyone there seemed to be writers. I begged my way in to a poetry workshop a semester later. I have never stopped writing since that workshop. I cannot not write.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Yes. And no. The core of lyric is figurative language, and I cannot teach someone how to come up with metaphor. I cannot teach a young fiction writer where to find her story. But one can teach craft. One can give a student a foundation in craft so that if and when they find what it is s/he needs to write, they have the tools to do so well. I believe that. It is why I teach creative writing at Warren Wilson most years.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

There is just too much great work out there for me to list five creative works, so I will name five books I ask students to read because they help to provide all of these tools I mentioned:

- The Art of Syntax, by Ellen Bryant Voigt

- The Art of the Poetic Line, by James Longenbach

- The Poetics of Space, by Gaston Bachelard

- Best Words, Best Order, by Stephen Dobyns

- The Art of Time in Fiction, by Joan Silber

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

When I admitted to my teacher, Donald Justice, that I feared going to medical school would be the end of me as a writer, he said “We always find time to do the things we want to do.” This rather simple sounding phrase gave me permission to live my life, to become a physician without giving up my desire to write. All throughout our history, writers have held many professions and jobs. Today, so many are told, either directly or by example, that to write means to become a teacher of writing. I say: do what you love. Do what feeds you. My mother says “You are dead much longer than you are alive,” and she is right. If you want to write: read, read, read, write, revise, and read some more. Make it your life and not just something to be done. And when it comes to work, do what makes you happy.

What are you working on now?

I am writing a novel, a prequel of kinds to my linked collection of stories I finished not too long ago. I thought I was done with the characters in that collection, but I wasn’t. The novel goes back three generations before the main characters in the story collection and moves toward the events of the story collection. I used to say I would never write a novel. I think from here on out, I am just not going to use the word “never.” If I use it, I am bound to violate whatever it is I say I will never do.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

Write a poem using the future tense. American poetry is obsessed with the present tense and its immediacy, but each tense carries its own power. There are things you can do using past tense that are not possible in present tense. And of the tenses, future tense is least used. So, I would prompt a student to try writing a poem entirely in future tense. One might not get a poem out of it, but it is likely to fire some new synapses in the brain and possibly even show a tool one can use later in writing other poems.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- Identify the pattern of rhymes in C. Dale Young’s “Cancer and Complaint at Midsummer.” How do these rhymes unfold? What do they teach us about the argument of the poem and the feelings of its speaker? How do you understand the line, “my mind now weak in handling form,” in light of the poem’s formal agenda?

- Discuss the effect of the syntax in the excerpt from “Torn.” What feeling is created by the structure of these sentences? Why does the poem return to a declarative mode (“there was…”) at the end of the poem?

- Discuss the evolving role of secrets in “Eclipse” by C. Dale Young. How does the poem use the image of light to complicate this?

- Several of C. Dale Young’s are written in tercets, stanza groups of three lines each. What effect does this arrangement have on the poem?

- In his Lightbox interview, C. Dale Young writes that, “We are wired, I believe, to look for connections. We all draw from our lives, both real and imagined.” How does his poem, “Proximity,” look for connections between disparate sources? What are the kinds of subjects that you draw from and reach toward as a writer?

- Reflect on what relationships exists between poetry and medicine as healing arts. You might look at “Torn,” specifically, and think about the ways the poem, as an act of writing, attempts to stitch up the patient, to put the body back together.

- Describe the relative presence and absence of the body in C. Dale Young’s poems, “Cancer and Complaint at Midsummer” and “Torn,” and “Proximity.” In what ways does the poet make the body alive for us, as readers? What is withheld about these bodies? What effect does this balance between absence and presence have on the poems he writes?

In-class Activities

Mysteries of the Body

In his Lightbox interview, poet-physician C. Dale Young describes the many connections he sees between the mysteries of medicine and the mysteries of poetry: “The mysteries are no more profound in medicine than in poetry. I question, and I doubt, and I think.” In this in-class activity, we’ll question, doubt, and think about the realms of knowledge we bring to understand what is mysterious, what is intelligible, and what is inexplicable about the human body.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt

Write about an aspect of the body that mystifies you. What is it that you want to know about the function, the strangeness, the grotesqueness, the beauty, the inexplicability of the human body? As you write, think about how you want to handle mystery in the poem, how you feel about existing in a space of uncertainty and unknowing. You might incorporate knowledge from medicine, such as terminology or light research, or you might choose instead to focus on your own observations. To further challenge yourself, you should apply the following constraints: Open the poem with a short, imperative statement, like “Admit it.” Also, use the same quote of direct speech at two different moments in the poem.

C. Dale Young’s Prompt

Write a poem using the future tense. American poetry is obsessed with the present tense and its immediacy, but each tense carries its own power. There are things you can do using past tense that are not possible in present tense. And of the tenses, future tense is least used. So, I would prompt a student to try writing a poem entirely in future tense. One might not get a poem out of it, but it is likely to fire some new synapses in the brain and possibly even show a tool one can use later in writing other poems.

Buy The Halo by C. Dale Young

Buy The Halo by C. Dale Young

[…] “Today, so many are told, either directly or by example, that to write means to become a teacher of writing. I say: do what you love. Do what feeds you.” Read more from C. Dale Young at the exciting new website Lightbox Poetry. […]