“…witness for me is the audacity to live and write during these times where my having breath frightens people”

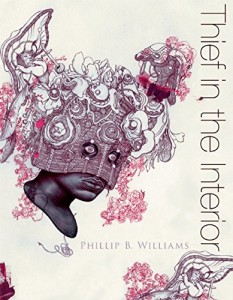

Phillip B. Williams is a Chicago, Illinois native. He is the author of Thief in the Interior (Alice James Books, 2016). He’s also co-authored a book of poems and conversations called Prime (Sibling Rivalry Press). He is a Cave Canem graduate and received scholarships from Bread Loaf Writers Conference and a 2013 Ruth Lilly Fellowship. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Anti-, Callaloo, Kenyon Review Online, Poetry, The Southern Review, West Branch and others. Phillip received his MFA in Writing from the Washington University in St. Louis. He is the poetry editor of the online journal Vinyl Poetry.

![]() What is a poem of witness? What makes it distinct from, say, a poem that recounts a memory, or a poem that engages with an historical event?

What is a poem of witness? What makes it distinct from, say, a poem that recounts a memory, or a poem that engages with an historical event?

1300, “bear testimony,” from witness (n.). Meaning “affix one’s signature to (a document) to establish its identity” is from early 14c. Meaning “see or know by personal presence, observe” is from 1580s. Related: Witnessed; witnessing.

Old English witnes “attestation of fact, event, etc., from personal knowledge;” also “one who so testifies;” originally “knowledge, wit,” formed from wit (n.) + -ness. Christian use (late 14c.) is as a literal translation of Greek martys (see martyr). Witness stand is recorded from 1853.

Those above definitions are from etymonline.com. The most recent verb form of the word steers us towards the act of seeing something and then testifying toward what was seen (i.e., witnessing an atrocity). It requires one’s body to be within or near enough to the situation about which the person will speak. So there is also a direct yet unspoken correlation to authenticity. “You weren’t there so how would you know?” is one way a person could argue against poetry that deals with perceiving a moment that is impossible for the poet to perceive because they were not physically present.

In many ways, this speaks to the imaginative inexhaustibility of a moment like Hurricane Katrina or the murder of Michael Brown or the earthquake in Haiti or nuclear meltdown in Japan, where these moments are simultaneously removed from their realities and flexed in the imaginations of the writer who then rewrites the moment without consideration of how that erases people for whom these events were and still are—if we consider trauma for a moment—a lived experience. It could feel noble to write poems that bring attention to something terrible that has happened somewhere in the world, perhaps even to people we know; however, one must be careful to make sure that they understand the unsteady reliability that is our own perception: if it is difficult to get it “right” when one is part of an event, then how “right” can a poet render what they have not seen or experienced?

So the most useful definition of witness for me is the audacity to live and write during these times where my having breath frightens people (or so they say). It also means to transcribe and through rigorous revision transform our lived experiences into something that elevates the lives of other people, often times by destroying everything they’ve learned to love and show loyalty toward. To be a poet of witness is to unapologetically be a syndrome of annihilations against erasure and illusion, which means that it requires self-reflection.

“Why am I compelled to write about this moment I have or have not lived?” is a more important question, in my opinion at least, than “How will I write about this moment?”

Today I would say that writing towards memory or a historical moment sits beneath the umbrella that is “poem of witness.” The question within the question of “What is a poem of witness?” is “When are we not witnessing?” I think there is a conflation between “witness” and “political,” as though apparently political poetry that deals with a current event or civil unrest is a poem of witness. But watching my sister’s dog die is also something I’ve witnessed. Kissing that just-dead dog on the forehead is something I did. Burying her after is also part of that experience. Is that not also part of me? Is that not political?

![]() In your book, Thief in the Interior, how do you imagine the form of a poem helps to advance an argument you’re making?

In your book, Thief in the Interior, how do you imagine the form of a poem helps to advance an argument you’re making?

The forms are ever-changing and for me that pushes on the idea that we can’t get it “right.” Even when looking for order and patterns, perhaps even finding them, there is beneath that the source of the interrogation which is chaos itself. That is, for me, what initiates the poem and form only helps to transcribe that there is indeed restlessness beneath the subjects. The book is all about failure, about the grotesque and what could be made beautiful from the grotesque. Form is simply one way of figuring it all out, an equation but not necessarily an answer.

![]() Your book deals with really significant historical and personal material. Why did you choose to express it in poetry instead of another medium?

Your book deals with really significant historical and personal material. Why did you choose to express it in poetry instead of another medium?

Prose was my original medium, fiction to be exact. I always wrote in verse but I didn’t take it as seriously as I do now until college. Even still I wanted to write stories for a living. So the choice of expression is simply one of timing, where my desire to write poems after having invested so much in learning about it (I have no M.F.A. or formal study in fiction) took over. I’m sure I could write about many of these things in fiction, too. It might not be as good but that is subjective and not really important to me right now.

![]() Your book was originally titled Witness? Why was that, and why did you ultimately decide to change the title?

Your book was originally titled Witness? Why was that, and why did you ultimately decide to change the title?

The original title was protean. Witness is simply the most recent rejected title. The book was once named Sway, Grace, Dancing on an Upturned Bed, As We Mourn Our Bodies, Darling, Empire, Empire No Empire, Empire, and possible some others I just cannot remember right now. Witness didn’t make it because it pointed too directly to the main concern of much of the book, which is what do we witness and how and what does that even mean?

![]() How do you incorporate extra poetic material, and do you think that’s necessary in a poem that seeks to bear witness to something that actually happened?

How do you incorporate extra poetic material, and do you think that’s necessary in a poem that seeks to bear witness to something that actually happened?

I think in writing the poem Witness in particular, which speaks to the unsolved murder of Rashawn Brazell, that using newspaper articles and interviews were responsible. It wasn’t about writing a poem that required those things. I had no idea where the poem was going only that it was going. It had reached the length of being about 20 pages and was on its way to being itself a long-poem book. That’s just how invested I was in writing the piece, which was originally called Thief in the Interior and that title was taken from yet another manuscript I’ve since abandoned.

But, as I was saying, the other resources were me trying to make sure I got what I could right. I didn’t want to misspell a name or get a date wrong and even still that happened in some cases that I hope I corrected in time for the book’s publication. I wanted to at least try to be the witness that Brazell never had as there were no witnesses to his death. The sections in the poem subtitled “witness” are all false, my hope that someone (and in one case something) somewhere saw what happened.

![]() What are the ethical dimensions of writing a poem of witness? Were there any moments in this book where you felt an ethical dilemma? Are there parts of the book that might have appeared, or appeared differently, but do not?

What are the ethical dimensions of writing a poem of witness? Were there any moments in this book where you felt an ethical dilemma? Are there parts of the book that might have appeared, or appeared differently, but do not?

I’ll answer the last question first: yes. The poem Witness would be much longer had I not edited it down to 15 pages. It was always meant to echo a crown of sonnets being in sections that culminate into a sonnet that closes out the entire poem, but making the poem actual 14-ish sections helped with that, and I hope that resonates throughout.

As far as ethics, what are the ethical dimensions of writing any poem at all? I mean, surely that this is a real story and that people related to the story are still alive is of incredible importance and caused me much anxiety. I wanted to at one point reach out to Rashawn Brazell’s mother, Ms. Brazell-Jones, and let her know that I was writing this long poem about her son’s death.

What stopped me was the sense of throwing her son’s death in her face, again, after 10-going-on-11 years of Brazell’s murder. It felt cruel to remind her that he is still without justice, so I just wrote the poem to educate other people about this still little-known case. The ethics become more concentrated; unlike a poem about a natural disaster, this poem has a single victim whose death created other living victims, people who will feel his one death forever. That level of intimacy and vulnerability is something I did not want to ignore. All I want to do is honor Rashawn Brazell and acknowledge that what happened to him was beyond words and, too, that his mother deserves peace. How in demanding peace for someone does that simultaneously run the risk of removing peace? That was my biggest dilemma.

![]() Can you talk about the forms of the poems that take the shape of circles? How did you come up with the idea of writing “Inheritance: A Spinning Noose Clears its Throat,” which is in the shape of a noose, and “Inheritance: Anthem,” which are these poems written within a circle of words?

Can you talk about the forms of the poems that take the shape of circles? How did you come up with the idea of writing “Inheritance: A Spinning Noose Clears its Throat,” which is in the shape of a noose, and “Inheritance: Anthem,” which are these poems written within a circle of words?

“Spinning Noose Clears its Throat” is an older poem. I think I wrote it in 2010 and I wrote it with slavery as the theme. It wasn’t until after Trayvon Martin’s murder that I updated the poem to be about how Black people are treated today in this new Jim Crow style of “justice,” not to be mistaken for the prison-focused book The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, rather the idea that racism has a new face and that face is the same face it’s always been writ large. It’s about the systemic circumstances being the same and therefore the noose has become the bullet, the ballot, the cities in which we live, and the absolute refusal of many people to acknowledge that race issues are a major problem in American’s psyche and neither turning colorblind (“I don’t see color,” or “I’m not a label”) or stubbornly/hatefully holding on to bigotry will make it easier to live. History repeats because people do not want to change the depth, only the surface.

“Inheritance: Anthem” was written after a very close friend of mine was arrested during a protest in St. Louis. I had visited the city after traveling around the country looking for a potential new home and needed to see a good friend of mine. So I stayed with him for about a month, maybe a few weeks, and early on in my visit he was arrested. What many people do not know about me is that I have bouts of anxiety, mainly in crowds but especially around loud noises and many moving bodies. So, going to protests send me spiraling into panic with or without any sense of danger. I went to one with my friend and it took a lot to be there. I was too focused on counting how many people were there to even want to put my fist in the air and chant. All of this leads to my writing the poem because it came out of a sense of being powerful, full of anxiety, and depressed.

So the poem is basically a ring of the Miranda rights encapsulating different verse structures that deal with police brutality, assumptions about race, and exhaustion with dealing with race deniers. As the poem proceeds the circle tightens, the Miranda Rights widening to become more readable but never 100% readable. The tightening is how I felt, the circle a cage, a handcuff, a faulty halo that is supposed to be the righteousness of the law constricting rather than protecting.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

I always wrote poetry, even in grade school. I took writing workshops in undergrad and was suggested by many poets—in particular Tyehimba Jess, Janice Harrington, and Alan King—to apply to Cave Canem. It took Janice to reveal that she was a Cave Canem fellow for me to finally apply.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

If learning how to play the piano can be taught then why not? I learned how to dance in undergrad. I also had a natural talent for drawing, which I no longer have. I think if people nurture an interest then anything is possible. Who am I to say that everyone whom I love to read was never taught how to write? How would I know that? I know that I always enjoyed writing and can argue that I’ve always been good at it, but had I not taken workshops and read feverishly throughout my life, I would still be at that primary level. Something taught me better. I may not be able to say who or what, but something did. I have no interest in being a special snowflake.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

There are absolutely more than five. Absolutely more. I will just list the first five that I think of, which may or may not be useful:

- Coin of the Realm by Carl Phillips

- Notes from a Divided Country by Suji Kwock Kim

- Collected Poems of Octavio Paz

- Drumvoices by Eugene Redmond

- Solar Throat Slashed by Aimè Cèsaire

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

Read. Everything. Read more than you write.

What are you working on now?

Nothing right now. I know that is not the standard answer but I am honestly just catching up on much needed reading. Poems seldom come.

Can you give us a poetry prompt for our students?

One that I do with my students in groups of 3-4 is for them to create their own forms. Surely this can be done alone. I suggest first reading poems that are in form, many of which can be found in Eavan Boland’s and Mark Strand’s anthology The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. Study the rules of the poems included there and practice writing the forms.

Whenever you are comfortable, try to create your own form. Give it a name and give it rules. How does the name reflect the rules of the poem? What form does the poem take on the page? What are the formal devices (rhyme, repetition, elision)? What do the rules suggest are the reasons for the form to exist (love poem, angst poem, poem about an obsession)?

Not a prompt as much as it is a long-term assignment.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- In his interview, Phillip B. Williams claims that the question for him is not, “How will I write about this moment?” but rather, “Why am I compelled to write about this moment I have or have not lived?” Think of some of your recent poems. What was it that “compelled” you to write about them?

- Discuss the balance of statement and description in “Vision in Which the Final Blackbird Disappears.” What effect does this balance have on the poem’s movement?

- Why do you think the body at the center of “Vision in Which the Final Blackbird Disappears” becomes monstrous? How does the description in the poem signal these transformations?

- Describe the ways in which “Theory of Moths” merges the erotic and the political. How does Williams use imagery, specifically, to draw connections between these elements?

- Compare Williams’s treatment of the body in “Speak” and “Theory of Moths.” How do elements of the poem’s different forms enact their respective intellectual and emotive claims.

- Read and look at “Inheritance: Anthem.” What do you notice about its visual arrangement? What do you make of the fact that parts of the poem are moving through a circle containing the language of the Miranda Rights?

- In what ways do Phillip B. Williams’s selection of poems correspond to his and Tarfia Faizullah’s definitions in their Lightbox interviews?

In-class Activities

Public and Private Memory

In his interview, Phillip B. Williams speaks about his poetic engagement with news documentation of the unsolved murder of Rashawn Brazell. In writing his long poem, “Witness,” he sought to “at least try to be the witness that Brazell never had as there were no witnesses to his death. The sections in the poem subtitled “witness” are all false, my hope that someone (and in one case something) somewhere saw what happened.” In this activity, we’d like you to respond and incorporate news and media documentation of an event that impacted your own life.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt

Choose a non-literary format of text you encounter often. It could be a business letter, an advertisement, a webpage, a recipe, a series of tweets. Think about how the text presents information, how its creator arranges the information visually/spatially, as well as the quantity and quality of that information. Write a poem that takes the form of this text. How can the conventions of another format create poetic possibilities? How can you stretch the bounds of what a poem might be? For inspiration, you could consult Phillip B. Williams’s sequence, “Witness,” from Thief in the Interior.

Writing Prompt Courtesy Phillip B. Williams

One that I do with my students in groups of 3-4 is for them to create their own forms. Surely this can be done alone. I suggest first reading poems that are in form, many of which can be found in Eavan Boland’s and Mark Strand’s anthology The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. Study the rules of the poems included there and practice writing the forms.

Whenever you are comfortable, try to create your own form. Give it a name and give it rules. How does the name reflect the rules of the poem? What form does the poem take on the page? What are the formal devices (rhyme, repetition, elision)? What do the rules suggest are the reasons for the form to exist (love poem, angst poem, poem about an obsession)?

Not a prompt as much as it is a long-term assignment.