“Playing with sound like that keeps a poem on its toes. But, for me, it can’t only be about sound. You have to have something to listen to; but, you’ve got to have something to see and sense, and something to care about and follow.”

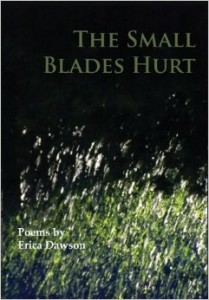

Erica Dawson is the author of two collections of poetry: Big-Eyed Afraid and The Small Blades Hurt. Her work has appeared in Best American Poetry, Birmingham Poetry Review, Harvard Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and many other journals and anthologies. She’s an assistant professor of English and Writing at the University of Tampa, where she serves as Director of the Low-Residency MFA in Creative Writing.

![]() Do you remember an early experience of working in traditional form?

Do you remember an early experience of working in traditional form?

Absolutely. The very first poems I wrote as a kid were formal in a child-like way. A lot of rhyming quatrains. My mom read to me and my brother all the time, so the poems often sounded like nursery rhymes or had a regular rhythm like Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride,” one of my favorites.

A grown up story? In college, I attempted a sonnet in my Introduction to Poetry class. It was about my cat. God awful. The next real attempt was in a later course. The professor had us imitate an author. I was obsessed with Merrill at that point and wanted to do something similar to his work, in terms of its honesty and sense of authenticity. I wrote about a recent experience where I thought a tumor I had was malignant (it wasn’t). Writing about it was almost too much to deal with. I had to rein it in somehow. So I turned to form for some kind of sense of control and confinement. It was a rhyme scheme I made up.

![]() Is there a received poetic form you are particularly drawn to and why?

Is there a received poetic form you are particularly drawn to and why?

I’ll always love my rhyming quatrains. They sound like songs. My ear can’t get enough. I’m always going to be into sonnets, too, especially crowns of sonnets. I love the rhetorical structure hinging on that volta. And it’s amazing how you can fit a little narrative in such a short poem that makes a statement. The end of a good sonnet is always a punch in the gut, mic drop moment.

![]() What advice would you have for a young writer scared of or intimidated by formal poetry?

What advice would you have for a young writer scared of or intimidated by formal poetry?

It’s hard work, but not nearly as scary or stifling as you think it’ll be. It won’t change who you are. It’ll make you reconsider all the things that come out of your head and onto the page. It makes you an amazing editor and critic of your own work. Do it. You don’t have to do it all the time. But you’ve got to try it sooner or later.

![]() As you draft a poem, how do you balance your allegiance to traditional or received forms with language that feels contemporary? How do you mix registers of language in a single poem?

As you draft a poem, how do you balance your allegiance to traditional or received forms with language that feels contemporary? How do you mix registers of language in a single poem?

In some ways, it just happens. That’s an annoying answer, I know. But it’s kind of reflective of who I am: a 35 year old woman living in 2015 who happens to love John Donne and George Herbert. It all just goes together in my head. That said, though, it’s just fun to do. So many people think form is dead (someone actually told me that once) or stale or super white. It’s poetry. And if you’re writing it now, it’s going to be contemporary, you know?

![]() Your poems are so sonically dense, richly textured—is there a way, when you write, you’re being driven as much by sounds as by narrative or imagery?

Your poems are so sonically dense, richly textured—is there a way, when you write, you’re being driven as much by sounds as by narrative or imagery?

Oh yeah. The sounds matter so much to me. Sounds can be so luscious and equally beautiful when they’re discordant. I love the echo of a sound we expect with a received rhyme scheme. If it’s a villanelle and you know how it works, you’ll know that the sound at the end of the first line will come right back at you in just a bit. And I love an unexpected rhyme when it pops up in the middle of a line. Playing with sound like that keeps a poem on its toes. But, for me, it can’t only be about sound. You have to have something to listen to; but, you’ve got to have something to see and sense, and something to care about and follow.

![]() Would you describe the process of writing, “If My Baby Girl is White”?

Would you describe the process of writing, “If My Baby Girl is White”?

After I wrote “Little Black Boy Heads” about a son I don’t have, I wanted to write some kind of companion piece. At some point I became obsessed with Lucille Clifton and “My Dream about Being White.” I was like, let’s write about an imaginary daughter and make her white. I didn’t want to be super explicit about it, though. I wanted it slightly under the surface. Thinking about stereotypes, I remembered that horrible phrase, “splitting oak,” usually referring to a white man having sex with a black woman. I moved on from there, holding on to the image of the tree as it rots but people don’t ever really notice.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

From my mom reading poetry to me as far back as I can remember.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Yes. It’s like music: you can’t teach innate talent; but, you can teach someone the scales and chords and they will learn how to make them their own.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

I’m old school so I’ll go old school. That said, there are tons of books in the last 2 years that people have to read, too.

The Riverside Shakespeare (expensive but totally worth it)

Lowell’s Life Studies

Bishop’s Collected Poems

Clifton’s Blessing the Boats

Walcott’s Omeros

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

“The role of a writer is not to say what we all can say, but what we are unable to say.” Anaïs Nin

What are you working on now?

Not much, sadly. I recently became director of UT’s low-res MFA. But I’m getting back in the swing of things, writing poems without thinking of them as a project or manuscript—just as poems. A lot of them seem to be mad at Jesus. Really mad.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

It sounds awful, and it’s super weird, but look at Levertov’s “A Day Begins.” Write your own poem where an animal is dead or dies. It’s going to seem gratuitous and maybe silly; but, being able to look at a death that isn’t human but is just the same as human…there’s always something poignant there.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- What is the relationship between the title and the text of “If My Baby Girl is White”? How does the poem tell a story? How does the poem function like an if/then proposition?

- Describe the various ways “If My Baby Girl is White” make use of rhyme. You might use different shapes or colored pencils to trace the patterns of consonants and vowels, as well.

- “If My Baby Girl is White” begins with an epigraph from the Lucille Clifton poem “my dream about being white.” Read “my dream about being white” and discuss any resonances you see between these two poems.

- “Florida Funeral” is full of interesting, sonically rich words—some of which seem obscure or specific to a place or body of knowledge. Make a list of the words you don’t know in the poem. What is their effect on you? What do you imagine they mean? Look them up in a dictionary and reread the poem. Has the effect of the poem changed for you?

- Take a quick look at the Dr. Seuss’s book, One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish, if you don’t know it already. What does Erica Dawson’s “One Fish Two Fish” take from the Seuss original? What do you make of the poem’s invocation of a children’s book?

In-class Activities

In this activity, students will think about the relationship between a poem’s sounds and its meaning. The class will talk about what other connective tissue exists between two words that have a sonic relationship in order to consider how those connections might lead to productive and interesting poems that make use of sound and rhyme.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt:

In her interview, Erica Dawson talks about the suggestiveness of sound in poetry: “Sounds can be so luscious and equally beautiful when they’re discordant. I love the echo of a sound we expect with a received rhyme scheme…Playing with sound like that keeps a poem on its toes. But, for me, it can’t only be about sound. You have to have something to listen to; but, you’ve got to have something to see and sense, and something to care about and follow.”

Write a poem in which you’re guided by sound, in which sound leads you to new images and metaphors in your writing. In your pre-writing, consider two words that share similar sounds—a rhyme, vowel sounds, or consonants—and then brainstorm about what else they might have in common. For instance: a parrot might eat a carrot; a parrot’s feathers might be bright orange like a carrot; a parrot molts and a carrot is peeled; and so forth. You can use the Lightbox activity, “Making Sense of Sound,” to help you. As you write your poem, think about what possibilities for connection you can find between your initial word and the new words you’ve decided on because of what they share in sound.

Erica Dawson’s Prompt:

It sounds awful, and it’s super weird, but look at Levertov’s “A Day Begins.” Write your own poem where an animal is dead or dies. It’s going to seem gratuitous and maybe silly; but, being able to look at a death that isn’t human but is just the same as human…there’s always something poignant there.

Erica Dawson Online