“I’ve always thought of them, of the poems, as being very private investigations and negotiations of a space that I can’t quite figure out—they’re where I wrestle with what I both resist and am drawn to.”

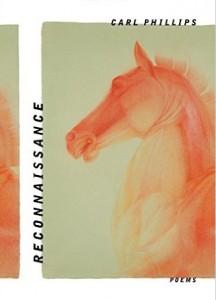

Carl Phillips is the author of thirteen books of poems, most recently Reconnaissance (FSG, 2015) and Silverchest (FSG, 2013). Phillips has also published two books of prose, The Art of Daring: Risk, Restlessness, Imagination, and Coin of the Realm: Essays on the Life and Art of Poetry; and he is the translator of Sophocles’s Philoctetes. His awards include the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Poetry, the Kingsley Tufts Award, the Theodore Roethke Memorial Foundation Award, the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry, the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Male Poetry, as well as fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Library of Congress, and the Academy of American Poets. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as the judge for the Yale Younger Poets Series, Phillips is Professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis.

![]() How do you see your amorous and erotic poems fitting into a tradition of love poetry? What resources do you draw on, as influences?

How do you see your amorous and erotic poems fitting into a tradition of love poetry? What resources do you draw on, as influences?

The first poetry in the love poetry tradition that I encountered was probably the fragments of Sappho. To me, they seemed not just love poems, but political poems, insofar as they were an assertion on the individual’s right to love, and to love whom she wished. I suppose I think my poems speak a bit to that tradition, to the extent that they are often homoerotic—and despite the various advances when it comes to sexuality, there still seems a need to speak honestly about one’s sexuality, as a possible model and inspiration for others, or maybe as proof that others aren’t alone…As for resources—in terms of content—I pretty much draw upon my life and upon the lives of those I observe in the world, which can include anything from actual people to situations found in novels, movies, etc. In terms of how to make a poem, the influences are countless. Lately I’m very interested in how sentences make for the musculature of a poem, which has led me to revisit the work of Kathleen Graber, Kathleen Peirce’s The Ardors, Adrienne Rich’s XXI Love Poems, and Virginia Woolf’s The Waves…

![]() Do you think the function of the love poem has changed, now that we have more complexly constructed identities surrounding desire?

Do you think the function of the love poem has changed, now that we have more complexly constructed identities surrounding desire?

No, I think the functions remain the same—to avow, to lament, to petition, to negotiate, to navigate. The increased complexities of identity mean, to me, that there are all the more lenses through which to see those functions that have become, over time, the tradition.

![]() Is there something native to poetry that makes it particularly or uniquely fertile ground for examining and transforming the experience of desire?

Is there something native to poetry that makes it particularly or uniquely fertile ground for examining and transforming the experience of desire?

I’d say there is something native to lyric poetry, yes—the tension between limited space and irresolvable (hence, limitless) abstraction. What I think this ends up meaning is that lyric poetry is particularly suited to the subject of desire, yes, but also the subjects of loss, death, joy, justice, shame—all the big abstractions.

![]() Do you remember, early on, when you began writing, a breakthrough moment in expressing or confronting something important about love and sex on the page?

Do you remember, early on, when you began writing, a breakthrough moment in expressing or confronting something important about love and sex on the page?

Probably that moment occurred when I was involved in my first real experience of desire with another man—it was an impossible situation for many reasons, not least of which was that I hadn’t come out to myself as a gay man yet—it wasn’t something I had come to understand. I have said elsewhere that I feel that poetry in some respects saved me. Having nowhere to turn, having no sense of how to move forward with a life, for some reason I started writing the poems that would become my first book. I hadn’t written in about ten years, and had had no further desire to do so. I think writing became the place where I first wrestled meaningfully with my own sexuality and, by extension, my ideas about love and sex.

![]() You’ve said before that syntax can function seductively. Could you talk about how syntax functions in “Capella”?

You’ve said before that syntax can function seductively. Could you talk about how syntax functions in “Capella”?

For the most part, I don’t think syntax plays a large part in that poem. In part III of “Capella,” there’s the long sentence that begins with the second stanza and introduces the idea of the dark as being erotic, followed by a suspended clause between the dashes—I sometimes think that the ability that syntax has when it comes to suspension and inversion, including here how the idea of power is held off until the end of the clause, can be an enactment of foreplay, of the stalling that goes with that…But overall, I’d say the real muscle of “Capella” lies not in its syntax but in its grammatical choices, especially when it comes to grammatical mood: part I has a frame of two declarative sentences at top and bottom, with a center made up of a question that also is the longest sentence in the section. Part II opens with two declarative statements, followed by two fragments (absence of mood), and an interrogative conclusion. Finally, part III opens with a declarative statement, then the rest of the poem is fragments all the way to the end. For me, the result is a restlessness—enacted at the level of grammatical mood—that resolves (if that’s the word) in fragments, mere images, stripped of mood. That, for me, is another layer of narrative.

![]() “Neon” is a poem about an intimate encounter, and yet it also seems to draw in larger social and political concerns about gender, sexuality, power, and desire itself. How do you manage those impulses in a short poem?

“Neon” is a poem about an intimate encounter, and yet it also seems to draw in larger social and political concerns about gender, sexuality, power, and desire itself. How do you manage those impulses in a short poem?

Honestly? I have no idea! This is a poem whose opening sentence took me a long time to arrive at. Once I had that sentence, I went around saying it to myself for days. And then I pretty much sat down and wrote the poem flat out one evening. I never gave any thought to the issues you mention, social and political; I was most interested in the gesture of setting out on one’s own at the poem’s beginning, and the desperate scene of physical violence that closes the poem.

![]() Do you see one goal of your poems as redefining our cultural sense of queer sexuality?

Do you see one goal of your poems as redefining our cultural sense of queer sexuality?

I think I’d be in trouble if I ever consciously thought about my poems having any particular purpose, let alone one so large as “redefining our cultural sense of queer sexuality.” I’ve always thought of them, of the poems, as being very private investigations and negotiations of a space that I can’t quite figure out—they’re where I wrestle with what I both resist and am drawn to. I feel very fortunate that the poems have resonated with other readers—and if that has also meant that they’ve contributed to how we think about sexuality, queer and otherwise, then I’m very honored by that.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

My mother wrote poems and encouraged us to read poetry when we made our weekly trips to the library. We didn’t have a lot of books around the house, but some of the ones I remember most were collections of poems for children.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Technique can be taught—I’m teaching a seminar now on the history of prosody in English. It’s quite possible to teach meter, forms, etc., and fairly easy to learn those things. It’s also very possible—and essential—to learn these things through looking at models that have come before. So, I’d say yes, the elements of poetry—of creative writing—can be put before a person and that person can become competent at handling them. The thing that makes a poem truly lift off the page, though, isn’t a mastery of technique; it’s vision. And that cannot be taught. It can be recognized, when seen—and I think it’s the job of the teacher to try to see it, and then try to get the student to see it and to learn how best to harness that vision. But I believe it’s there or it isn’t. I also believe that vision doesn’t necessarily require instruction, at least not classroom instruction.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

That list would go way beyond five books, but I appreciate not having to list more than five! I guess my list—on this particular afternoon, at least—would include Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Homer’s Iliad, Augustine’s Confessions, David Young’s translation/anthology called Five T’ang Poets, and all of Chekhov’s plays. For me, these are all books that make me think about how the mind works, what it has meant to be a human being, which is to say, gifted and burdened by self-consciousness; they make me think what it has meant not just to have something to say, but to have said it.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

Alan Dugan once told me that I should bear in mind, when revising, that we often dream in the wrong order—when stuck on a poem, he’d say go home and redream it. Impossible advice, and yet somehow it’s stayed with me and been useful…As for my own advice to working young writers, read everything. Not very sexy advice, I’m sorry to say. But pretty useful.

What are you working on now?

I just work poem by poem, not with a book in sight. I finished a poem the other day. That means I probably won’t write again for a month. So my writing work is the work of reading—I’m finishing a novel by Patrick Modiano—and of being in the world, which this weekend means, I hope, going to a couple of harvest festivals around town. You never know where the next poem will come from…

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

I’ll preface by saying that I’ve never been able to write a poem to a prompt. But in the hope that it might be helpful to others, how about: Take two free-verse poems, each no longer than 15 lines long, and each looking and working radically differently from the other. For example, it could be a poem by Gertrude Stein and a poem by Jack Gilbert. Then, list three technical elements that are being employed in each poem. Then write your own poem of no more than 15 lines that uses a combination of these elements. Also, there has to be a rhyme somewhere. Also, an animal without teeth. Also freedom. No kidding.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- Which specific moments give us information about the emotional state of the speaker in “As from a Quiver of Arrows”? What emotional impression do they give us of this speaker? What’s his or her relationship to the other in the poem?

- To whom are the questions in “As from a Quiver of Arrows” addressed? Do you think this speaker imagines a listener? Do you think this speaker imagines there are answers to his or her questions?

- Phillips’s poems seem to have a fascination with power, both wielding it, and giving into it. Trace the shifts and dynamics of power in “Capella.” Which strategies and elements of the poem justify your thinking about these shifts?

- Carl Phillips’s often writes titles that have complex and indirect relationships to the texts of the poems. How is the promise of the title of “If a Wilderness” fulfilled in the poem itself? How does the poem complete the other half of an “if-then” proposition?

- Phillips’s poems seem to manage sound and silence very carefully. Follow moments of overt sound and silence through the movement of “If a Wilderness.” How does Phillips create more silent moments in the poem? Louder moments? How does the “score” of this poem affect its tone and mood?

- What are the different registers of language—bodies of knowledge, styles of speech, high and low diction—Carl Phillips engages in his poem, “Neon”? What effect does the mixture of the philosophical, the colloquial, even the profane, in a single poem have on you, its reader?

- Carl Phillips writes that, early on, he was drawn to Sappho’s poetry because her poems were not just love poems, but also political poems? In what ways might you read Carl Phillips’s poetry as political? How do his love poems reach out and think about the wider world, modern society, and human history?

In-class Activities

Style and Substance

In his Lightbox interview, Carl Phillips writes about the range of strategies he employs in his poem “Capella.” He makes note of how choices in grammar, syntax, mood, image, and narrative come together to create a feeling of restlessness in his piece. Good writers are able to think carefully about their own choices, and have some sense of their own poetic style. In this activity, we’ll think about Carl Phillips’s poetic style, as well as our own styles as writers.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt:

In his interview, Carl Phillips argues, “the functions [of the love poem] remain the same—to avow, to lament, to petition, to negotiate, to navigate.” For this writing assignment, draft a love poem that fulfills one or more of Carl Phillips’s definitions.

In addition, we will ask you to work with several constraints:

- The poem should be sixteen lines long.

- The poem should include at least three questions.

- The poem should include at least one sentence of direct address.

- The poem must include one sentence that stretches over four lines.

- The poem must use three nouns that appear in “As from a Quiver of Arrows” by Carl Phillips.

Carl Phillips’s Prompt:

I’ll preface by saying that I’ve never been able to write a poem to a prompt. But in the hope that it might be helpful to others, how about: Take two free-verse poems, each no longer than 15 lines long, and each looking and working radically differently from the other. For example, it could be a poem by Gertrude Stein and a poem by Jack Gilbert. Then, list three technical elements that are being employed in each poem. Then write your own poem of no more than 15 lines that uses a combination of these elements. Also, there has to be a rhyme somewhere. Also, an animal without teeth. Also freedom. No kidding.

Carl Phillips Online

Buy Reconnaissance by Carl Phillips

Buy Reconnaissance by Carl Phillips