“My poems were asserting that the military spouse has a right to speak and that her contact with war, while different from the soldier’s experiences in battle, may be equally intense, immersive, and life-changing. She too can write what we label as ‘war poems.'”

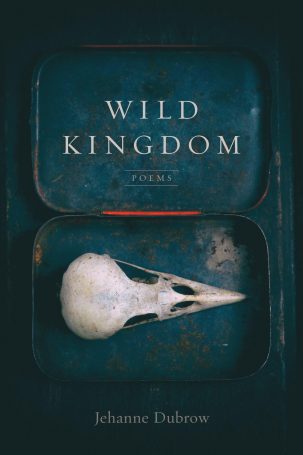

Jehanne Dubrow is the author of nine books of poetry, including most recently, Wild Kingdom (LSU Press, 2021), as well as a book of creative nonfiction, throughsmoke: an essay in notes (New Rivers Press, 2019). Her previous poetry collections are Simple Machines, American Samizdat, Dots & Dashes, The Arranged Marriage, Red Army Red, Stateside, From the Fever-World, and The Hardship Post. She has co-edited two anthologies, The Book of Scented Things: 100 Contemporary Poems about Perfume and Still Life with Poem: Contemporary Natures Mortes in Verse. Her poems, essays, and book reviews have appeared in numerous literary journals, including Poetry, Southern Review, Pleiades, Colorado Review, and The New England Review. Her work has been featured by American Life in Poetry, The New York Times Magazine, The Slowdown, Fresh Air, The Academy of American Poets, as well as on Poetry Daily and Verse Daily. She is the founding editor of the national literary journal, Cherry Tree.

Describe the process of writing “Against War Movies.” How did it come to take that particular form?

I wrote “Against War Movies” after my husband (who is career military) told me that he was being encouraged to do an individual augmentation, a little-known program that in the mid-2000s was sending Navy personnel to fill Army billets on the ground in Iraq and Afghanistan. The idea that my husband might experience this version of war and combat sent me into a deep depression. I was no longer able to compartmentalize my husband’s work as a Naval officer—imagining him aboard a ship, hidden away in the engine room—but could now see him embedded in a conflict that terrified me. Although the individual augmentation didn’t end up happening (military life is extremely unpredictable, with plans always changing), I began writing the poems that became my book Stateside. “Against War Movies” was the result of this sudden, sharp understanding of my husband’s service; nothing felt safe any longer. I couldn’t even watch the news or the History Channel or classic movies without seeing my husband in every soldier’s face. The poem is about imagination and empathy, how those two acts can create in the military spouse a terrible grief.

Do you see your work fitting into a tradition of war poetry?

Absolutely. Whenever I write a book, I do a tremendous amount of research in order to learn about the tradition I’m trying to enter. In the case of Stateside, I spent a great deal of time reading and thinking about the English-language poets of World War I (Owen, Sassoon), American poets of the Civil War and the Vietnam War (Whitman, Crane, Komunyakaa), as well as a contemporary soldier poet like Brian Turner, who in the mid-2000s, was viewed as a completely new voice in American poetry. I was very aware of the fact that I was writing from a perspective—that of the military spouse—which had been relegated to near-silence in the tradition of war poetry. My poems were asserting that the military spouse has a right to speak and that her contact with war, while different from the soldier’s experiences in battle, may be equally intense, immersive, and life-changing. She too can write what we label as “war poems.”

What is distinct about writing about wartime experience in contemporary times vs. poems in the wartime tradition?

What’s known as the “battle rhythm” has changed tremendously over the last decade. Soldiers are now experiencing more deployments in the space of a few years than, a generation ago, a soldier might have faced over his entire career. Soldiers are also surviving terrible injuries, because of improved Tactical Combat Casualty Care. This means that soldiers who would have died in earlier wars are now surviving. They’re coming home with physical or emotional wounds that may require a lifetime of treatment. The new war poems that soldiers and spouses are writing have to address subjects such as the lasting consequences of PTSD, traumatic brain injury, sexual assault overseas, the ethical ramifications of forced interrogation techniques, and the staggering numbers of suicides we’re seeing among veterans.

How have you used your work as a poet to reach out to and connect to military families and military communities? What response have you received from these groups?

Since the publication of Stateside in 2010, I’ve taught in writing workshops for veterans. I’ve been on scholarly and creative writing panels about war literature. And I’ve read from my work at military institutions, bases, and hospitals. I especially appreciate when there are other military spouses in the audience; their responses tend be extremely positive, even grateful (perhaps they’re relieved to encounter literature that finally voices their experiences, their points of view). The reactions of active duty military personnel tend to be more complicated. Some express support for the perspective that Stateside articulates, and some seem unsure that it’s appropriate for a spouse to speak in any tones but the most positive about the sacrifices military families are asked to make.

Was there any impulse in your writing of challenging some of the popular conceptions of war and the wartime hero?

Yes. And yes. Traditionally, military spouses have been expected to remain dutifully mute. Even expressing the idea that being “married to the military” is a difficult, sometime strained experience, might be perceived as unpatriotic. So, when I began to write poems like “Against War Movies,” I knew that I was breaking a kind of social contract which is imposed on military spouses. I felt that I should really commit to questioning some of the myths of military culture: the godlike hero, the fixed and unchanging military spouse, sacrifice as a reward in itself. This gave the poems—even those that don’t express a particular political stance—an edge, a feeling of friction. They’re working against a very seductive, romantic narrative about the heroic warrior and the ever-sacrificing wife left behind on the homefront.

What other kinds of media about the sacrifices military families make did you draw on in writing Stateside?

Stateside is informed by its conversation with other works of war literature, including Stephen Crane’s “War Is Kind,” Siegfried Sassoon’s “A Working Party,” and Homer’s The Odyssey, the last of which shapes the entire middle section of the collection. Film, music, and photography play important roles in the collection as well.

What role does gender play in the tradition of telling (or not telling) these stories?

When I began writing Stateside, there were very few women writing about the military spouse as a subject of literature. By the time Stateside was published in 2010, I joined a small group of women who were representing the experiences of military spouses in memoir, fiction, and poetry. But because I wrote Stateside within the relative isolation of my gender, the book is informed by the male perspectives of soldier-poets and by the masculine fantasy of female fidelity and stability, which is to say the figure of Penelope in The Odyssey. I wrote both to these male perspectives and against them. I now realize that I looked to male writers not only because they formed the central literary conversation about war but also because, in alluding to their work, I was (subconsciously) trying to give my own voice authority. Only later did I recognize this impulse to turn to male perspectives in order to endow my own verse with credibility. I’m now writing a “sequel” to Stateside, titled Dots & Dashes, which looks instead to female figures such as Sappho and Emily Dickinson for a different language of war.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

I can trace my roots in poetry back to my earliest contact with reading. I’m the daughter of American diplomats and spent my entire childhood moving from country to country. When I was five, we were posted to Communist-era Poland. It was a time before satellite TV or the internet. And Warsaw, in 1980, was a gray, sooty landscape, totally cut off from everything. As a way to entertain me, my father ordered the Time-Life cassette series dedicated to the “great American musicals.” Every month, a box of three cassettes would arrive, each set dedicated to a different or composer or composing team. Rodgers and Hammerstein. Rodgers and Hart. Lerner and Loewe. Gershwin. Berlin. I loved them all. But, Cole Porter was my favorite. I memorized all of Kiss Me Kate and Can-Can. A song like “Anything Goes,” with its quick, brilliant rhymes, is almost part of my DNA:

If driving fast cars you like,

If low bars you like,

If old hymns you like,

If bare limbs you like,

If Mae West you like,

Or me undressed you like,

Why, nobody will oppose.

When I teach my students a form like the ghazal, I show them these lyrics. The music of the two forms is nearly the same—the use of internal rhyme, the repetition of the end words. I think I became a poet who works in traditional forms, using rhyme and meter, thanks to Cole Porter who makes the pleasures of these formal constraints almost irresistible.

I wrote my first poem when I was twelve and kept writing throughout high school. After college, I had a very sad break-up (with the man who eventually became my husband, eight years later), and it was during this time that fell deeply in love with the study and writing of poetry. At the time, I was managing a chain of gourmet coffee shapes. In between pouring shots of espresso and steaming milk, I would read books about poetic craft. I gave myself writing assignments, including—for a year—drafting one Elizabethan sonnet per day. At the end of that year, I called my parents and told them I wanted to apply for “something called an MFA.” Not long after that, I began my graduate studies. Graduate school taught me craft and how to run a creative writing classroom of my own. But it was those years in the coffee shop that taught me self-discipline and the value of setting goals for myself, both as a reader and as a writer.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Technique can be taught. In the classroom, we can break down—for our students—how a literary device (such as an image or a metaphor) is made, the purpose these devices serve, and the reasons some fail and some succeed. Taste can be taught. A teacher can expose students to good writing, which in turn helps to train the eye to specificity and concreteness, tune the ear to musicality, shape the mouth to delicious speech. Maybe bravery and risk-taking and curiosity can be taught too, by example I think. Certainly, I try to model those things in the classroom for my students.

But, perhaps what can’t be taught is how to find one’s voice by discovering and writing towards one’s obsessions, the subjects that propel the work, giving it gravitational force and a reason to be. We each need to unearth our own obsessions—mine are loneliness, representations of trauma, and the intersection of personal and public histories—through introspection, through a close study of what we’ve written, what we’re writing, what we want to write. Not every aspiring writer wishes to engage in this kind of self-reflection.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

As an undergraduate, I went to St. John’s College, what’s known as the “Great Books School.” So, my required reading list centers on the importance of cultural literacy, on the benefits of having a really solid grasp of Greek mythology, the Bible, and the writings of Shakespeare. A few days ago, I was teaching a poem by Kim Addonizio, which begins: “Oh hell, here’s that dark wood again. / You thought you’d gotten through it– / middle of your life.” My students didn’t know that this was an allusion to Dante. On another day, we were discussing a short story by Lorie Moore, “Referential,” which is in many ways a performance of how a writer engages with the words of other writers. Near the end of the story, the narrator asks, “What would burst forth? A monkey’s paw. A lady. A tiger.” The students hadn’t heard of “The Monkey’s Paw” or “The Lady, or the Tiger?” Sometimes, I worry that my students feel excluded from the impassioned conversation taking place on the page. I want reading for them to be the companionship of literary conversation—writers arguing with another across continents and centuries.

That isn’t really an answer to your question! I can only pick five books? Here are the one that I revisit again and again: Selected Poems and Prose of Paul Celan (translated by John Felstiner), Gjertrud Schnackenberg’s Supernatural Love: Poems 1976-1992, Czesław Miłosz’s New and Collected Poems: 1931-2001, Thom Gunn’s Collected Poems, and Elizabeth Bishop’s The Complete Poems: 1927-1979.

Since those are all collected and selected works, my answer is a bit of a cheat. So, here are five poetry collections I’ve really loved over the past five or ten years: Claudia Emerson’s Late Wife, Beth Bachmann’s Temper, Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard, Tarfia Faizullah’s Seam, and Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (which is really a lyrical essay, but I count it as poetry).

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

Years ago, one of my teachers proclaimed: “No Bloodless Poetry.” I’ve kept this as my motto. I understand it to mean that writing is activity not only of the mind but also of the heart. When we write a poem, we engage with rhetoric and grammar, the intricacy of syntax. But blood has to pump through the poem too; it has to be a thinking, feeling thing.

What are you working on now?

I like to work on several projects simultaneously. It’s a way of avoiding boredom. Whenever I start to feel stuck on one manuscript, I’ll move to another—like a change of scenery. I’m currently finishing work on my sixth poetry collection, Dots & Dashes, which acts as a sequel to Stateside. I’m also writing another book of poems, tentatively titled Dinner with Kathleen Battle, which examines my father’s love of opera and discusses the ways this art form has become a part of my family’s culture and history. I am also working on a book-length essay; throughsmoke tells the parallel stories of how I fell in love, first with poetry and later on with perfume (and with smelling in general).

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

Before I began writing throughsmoke, I co-edited a poetry anthology called The Book of Scented Things: 100 Contemporary Poems about Perfume. My collaborator and I sent out individually selected vials of scent to each contributor. Here’s the prompt we gave them: “Please, write a poem that engages with or responds to the fragrance that we have sent you. The poem can be an interpretation of the scent, a memory, a series of associations, or some entirely different kind of interaction with the fragrance. You can wear the perfume or sprinkle it on your pillow or just sniff the scent in its glass vial—whatever works best for your process.” I often use this exercise in my creative writing workshop, giving each student a different perfume as a source of inspiration. Smell can be a powerful means to enter our stories and the stories of other people. Smell can be a gateway into the past or into imagination or into emotion. We privilege sight and often forget about our other senses. Smell reminds us that we are more than merely eyes; we are whole bodies.