“The irony is that, at least for me, it’s only distance that grants the clarity necessary to be able to write about any given thing.”

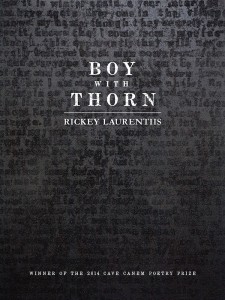

Rickey Laurentiis was raised in New Orleans, Louisiana. He is the author of Boy with Thorn, selected by Terrance Hayes for the 2014 Cave Canem Poetry Prize (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2015) and is the recipient of many other honors, including a Ruth Lilly Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation as well as fellowships from the Civitella Ranieri Foundation in Italy, the National Endowment for the Arts and Washington University in St Louis. His poems appear in Poetry, New England Review, The New Republic, Kenyon Review and Boston Review, among other journals and magazines. He lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

![]() Many writers have talked about “a sense of place” in their work. What, to you, is your “sense of place” as a poet? How can poetry be a space for imagining and reimagining places in our lives? Why do it?

Many writers have talked about “a sense of place” in their work. What, to you, is your “sense of place” as a poet? How can poetry be a space for imagining and reimagining places in our lives? Why do it?

Physically, I suppose the “sense of place” that most attends my poems would be the South. I was raised in New Orleans, and so that particular landscape has always been a part of my consciousness. But as I was being raised in New Orleans, I was also reading much of what is called Southern literature—Flannery O’Connor, Tennessee Williams, Zora Neale Hurston, et cetera—and so much of my sense of place is also in conversation with the South as seen and written via those writers.

For me, it’s important to remember that place in poetry is as much, if not more of, an imagined space as it is an “actual” description or representation of that place. There are already so many national fantasies and narratives about the south—some good or “mystical,” even majestic, others bad, or less attractive—and I think what some of those writers I mentioned above did in their work was use those narratives and build off and/or revise them toward creating their own stories. That’s what I’m interested in doing in my poems anyway.

![]() What do you hope to capture about a place—whether specifics of a landscape or, more generally, a sensibility—when writing a poem that invokes or references a landscape?

What do you hope to capture about a place—whether specifics of a landscape or, more generally, a sensibility—when writing a poem that invokes or references a landscape?

Mostly, I hope to capture how my particular mindset and sensibility regards or meditates on or negotiates a place. Really, I think that’s the work of literature—poems, specifically—that is, this notion how the world, or some aspect of the world, is filtered through a particular writer’s sensibilities, her eyes. So, for me, when I look at my given place or landscape—typically, the South—there’s a drive in me to present all the multiple ways I feel about that place, which is decidedly not always pleasant or good. The South, like any place, is a complicated, even contradictory landscape. It contains both violence and reverie, and I would say it often reveals both of these (at least historically) quite frankly.

![]() Is there any way you think your work speaks to a particular audience, among others, because of a sense of place it evokes?

Is there any way you think your work speaks to a particular audience, among others, because of a sense of place it evokes?

Yes and no. I think when evoking specific landscapes one, of course, seems to call up a certain audience that is familiar with or even from that place. But just as I said earlier, what I’m really aiming for is evoking that landscape as filtered through my consciousness, so that what I’m seeing is not exactly what another person might see or has seen or, even, wants to see. The trick is to find language both interesting, complicated and yet what—for lack of a better term—I’ll call “pure” enough that it resonates with someone outside myself. So, yes, I think it’s possible that my work speaks to particular audiences I have in mind, but it’s just as possible that it speaks to others that I never considered.

![]() Is your physical environment important to you as a writer in the act of writing? Are there certain places—a desk in your bedroom, a local coffee shop, a library—where you feel most productive, most artistically “at home”?

Is your physical environment important to you as a writer in the act of writing? Are there certain places—a desk in your bedroom, a local coffee shop, a library—where you feel most productive, most artistically “at home”?

I used to say no, that I find I could write in any place, but lately I’ve discovered that’s not exactly it. Really, I can’t write statically—I mean, at desk or table or in a park or anything like that. The work comes best when I’m somehow in transit: in a subway, on a plane or car. I also take a lot of walks and find that very conducive to writing. I write a lot in my head, repeating lines again and again, until they “click.” Then I move to any number of notebooks I have handy, and physically begin to write. It’s not until much later when I get to a computer to type what, by then, is usually a pretty finished draft. I don’t know what this says about me that I feel most artistically “at home” while in motion, but that’s how it is.

![]() Why do you use epigraphs, such as “New Orleans, 2005,” to place us before a poem begins? What kind of work do you expect that to do for a reader’s understanding of the poem?

Why do you use epigraphs, such as “New Orleans, 2005,” to place us before a poem begins? What kind of work do you expect that to do for a reader’s understanding of the poem?

It does, I hope, exactly what we’ve been discussing so far: establishes a sense of place for the reader. More, it not only gives an exact location, it offers a specific time I want the reader to consider, which has the effect of introducing the assault of history into a text. In this particular case, I want readers to recall Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in New Orleans in August of 2005. I want readers to have that episode of our recent American history in mind—and, with it, all the things they know or think they know about the event—and to come with all that into the door of the poem.

![]() Do you feel your geographic location—your proximity or distance from the places you write about—affects your writing about those places?

Do you feel your geographic location—your proximity or distance from the places you write about—affects your writing about those places?

Oh, yes. The irony is that, at least for me, it’s only distance that grants the clarity necessary to be able to write about any given thing. This could be a literal place, or it could an emotional state or important event in one’s life. It wasn’t until I left the South, left New Orleans, and moved as it were “up North” for college, when I could really begin to “see” New Orleans—or, better said, could begin to process through my ideas and notions of New Orleans. I cherish that distance. I think it’s crucial to the act of writing, and could also be crucial to act of reading. I know at least I’ve read several poems, and whether I thought I understood it or not, it wasn’t until putting the poem down, stepping away from it for a period of time, and returning to it when the poem really resonated with me, clawed inside.

![]() What is it like to write about a New Orleans that has been drastically altered in the wake of Hurricane Katrina? How do you want your poems to speak to that place as a dynamic and changing landscape?

What is it like to write about a New Orleans that has been drastically altered in the wake of Hurricane Katrina? How do you want your poems to speak to that place as a dynamic and changing landscape?

I was speaking to a mentor and former teacher recently who, like many people, had the experience of growing up as the child of a military parent. So, for him, he was constantly moving and changing landscapes, and to some extent without certain roots in one given place until he was much older. I don’t have that experience, but in talking to him I think I’m coming to see it as the closer analogue to my experience of Hurricane Katrina and its effect on New Orleans. It’s the experience of being from a place and then, suddenly, that place being caused to changed—radically, quickly—such that in some ways it’ll never be what you remember it as again. So I want to say, like the military child, I’m at work to get back to this remembered home that, in some way, doesn’t anymore exist.

I think my poems might get to this sense of restlessness formally. I’m interested in adopting all sort of formal constraints for my poem, whether in the initial genesis or later in revision. But also just as soon as I’ve “landed” on a given form, I’m still likely to change it until finally coming upon the final version. It’s a dynamic process that’s, really, very private—only someone watching my process over a span of time could see it happen. But I think, while reading over an arc of my poems, it’s possible to see it at work as well.

![]() Your poems are so gorgeous and lyrical, very song-like and prayer-like. What local and broader musical traditions are you drawing on in a poem such as “Crescendo”?

Your poems are so gorgeous and lyrical, very song-like and prayer-like. What local and broader musical traditions are you drawing on in a poem such as “Crescendo”?

Well, thank you! I don’t know if there’s exactly one musical tradition I’m drawing on. More likely, it’s the result of several traditions colliding inside my head or ear, as it were. I was raised Catholic, so there’s something about the solemn hymnals that still resides in me, but I was raised, specifically, in a black Catholic church, which is distinct, and so it was just as often I’d hear what we’d called Negro Spirituals or even what is Gospel in the mix of those hymnals. New Orleans is always already a very musical city. There are times of the year one can literally hear a brass band, some jazz or blues around any corner. I think all of this is at work, though unconsciously, in my work, and certainly a poem like “Crescendo” (which is a musical term) attempts to make use of that.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

Because I loved to read, I came to be envious of those who could create the stories that entertained me. So, I started to mimic them. At first, I thought the only way to be a writer was to write fiction, but when my mother gifted me a short collection of poems by Nikki Giovanni once I realized this wasn’t necessarily the case. I wrote a lot of poems throughout my adolescent years, but mainly privately, for myself or my family only. I was like the Emily Dickinson of New Orleans! Later, in college, I realized this was something maybe I could share with more people than myself.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Well, here’s the thing: writing can be taught. Physically, every human has to be guided on how to hold a pencil or pen, shape out the letters, spell out the words. Later, we learned parts of speech, how sentences work and for what effect. In tandem, we learn how to become better readers: asking questions as we read, making inferences and connections, building and supporting arguments based on the texts. In short, as we grow, we become literate, and come to understand language as a tool of communication with the world.

Now, to add the creative, to it is, for me, all about exposing the same human to artistic outlets, whether that be via stories and poems to mimic, or pieces of visual art, music, etc. It’s about guiding the person to begin to see how language, again as a tool of communication with the world, is also, simultaneously, a means of expression with her or himself, and the world. All the basic tools of our medium can be and are taught (just as they are for music, visual art, dance, etc), and we can be given access to creative or artistic pieces from which to draw inspiration. And from this place, I think, the creative writer—the person who chooses to be a creative writer—begins to teach herself.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

This is the hardest question! If I answer, the five would only really be a testament of the books that, somehow, I required to be the writer I am today, not necessarily the five books any other given writer requires. Instead of listing specific titles, I’d rather offer the general advice (or challenge) to remain open and diverse in one’s reading practices. Think for yourself which five books really left an impact on you, or take a glance at your book shelf. How many women are on the shelves? How many people of color? How many people who are not from the country of your origin, or those who love differently from you? It’s always insisted that we “write what we know” and whether or not it’s true, I know that it’s just as important to “read what we don’t know.” Our bookshelves should be a reflection of the world we live in, not just ourselves, our limited perspectives.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

The best advice I have for young writers, which was given to me, is to read twice as much as you write. For every story you write, you should have read or be in the process of reading at least two other stories. For every poem, the same. A library or bookstore is a writer’s greatest teacher and, in the end, may be her only one. Don’t be seduced by the idea that to read others’ work is to be potentially influenced by them. Be influenced. It’s only then that you can begin to make actual decisions in you writing, choices about how you want sentences to work and sound, voice and character to be developed, images and ideas to explore.

What are you working on now?

As always, I’m working on the next poem. And always working to better myself.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

This prompt is connected to something I just wrote for Poets & Writers here.

WRITING OBSESSIVELY

Keep a journal for a week where you will list at least ten obsessions. Think about not only physical objects that you own or would like to possess, but things that catch your eye, that you like to look at, that you wished you could own or possess. Think about things you wish you had the ability to make or things that, perhaps, you’d like to become. Think about things that you think about, ponder, worry over, abstract concepts or ideas. Think about things that frighten or terrify or even disturb you (fears or phobias can be obsessions of their own kind). Allow yourself to repeat entries if they truly obsess you. After a week, you should have a sufficient inventory of quick-fixes to the problem of “writer’s block.” That is, a list of objects, subjects or themes that you can always return to in your writing. To test this, pick any one of your listed obsession and, using language from answers to the following questions, write a poem.

- How were you first introduced to this obsession?

- How does this obsession make you feel?

- What form does this obsessions take? What does it look like? Sound like? etc.

- How does your mother feel about this obsession? Your father? A loved one?

- Is it right that you have this obsession? Should you feel proud? Ashamed?

- What in the world would you destroy in order to keep your obsession?Would you destroy anything in the world to keep your obsession?

- How would you describe this obsession and its importance to you to someone who doesn’t share your language?

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- In his interview, Rickey Laurentiis writes, “The irony is that, at least for me, it’s only distance that grants the clarity necessary to be able to write about any given thing.” Is there anything you feel too close to (or distant from) to write about?

- “Crescendo” by Rickey Laurentiis has the epigraph, “New Orleans, Louisiana August 2005.” His poem “You Are Not Christ” has the epigraph, “New Orleans, Louisiana.” What effect does marking a particular time or place in the epigraph have on your reading?

- What kind of meaning do you think you would glean from “You Are Not Christ” or “Crescendo” if you didn’t have any information about New Orleans, Louisiana in August 2005? What does that tell you about other layers of meaning in the poem?

- How would you describe the effects of the line to the music and to the meaning of Laurentiis’s poems? How do you read and experience poems differently that are written in stanzas and poems written in a single block of text?

- What is Southern about the poem “Southern Gothic“? What is gothic about “Southern Gothic”?

- Compare “Southern Gothic” with “Conditions for a Southern Gothic.” What do these poems seem to imagine a “southern gothic” is? How does the poem “Southern Gothic” speak back to the conditions explored in “Conditions for a Southern Gothic”?

In-class Activities

This exercise can be conducted in-class or for homework, in preparation for class discussion. Students will read several poetic responses to Hurricane Katrina as well as a variety of responses in other media (such as news articles or photo essays). The assignment encourages students to reflect on how poetry can differently engage such major events than other media, and to consider why we might choose to respond to them with poetry.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt:

In his interview, Rickey Laurentiis writes, “For me, it’s important to remember that place in poetry is as much, if not more of, an imagined space as it is an “actual” description or representation of that place.” Of his “homeplace,” Maurice Manning writes, “We all live in a specific place. What matters is if we notice, if we pay attention and learn to value our place.” Think about a place that is important to you. Perhaps it is the house where you grew up, a place where you created a favorite memory, or a space of quiet contemplation.

Write a draft in which you try to imagine this place as richly as possible. Make decisions about aspects of the place you will describe, aspects you will seek to represent, and aspects that will remain, for your reader, merely imagined. Experiment with using an epigraph that designates a specific place and see how the poem is affected.

Rickey Laurentiis’s Prompt:

WRITING OBSESSIVELY

Keep a journal for a week where you will list at least ten obsessions. Think about not only physical objects that you own or would like to possess, but things that catch your eye, that you like to look at, that you wished you could own or possess. Think about things you wish you had the ability to make or things that, perhaps, you’d like to become. Think about things that you think about, ponder, worry over, abstract concepts or ideas. Think about things that frighten or terrify or even disturb you (fears or phobias can be obsessions of their own kind). Allow yourself to repeat entries if they truly obsess you. After a week, you should have a sufficient inventory of quick-fixes to the problem of “writer’s block.” That is, a list of objects, subjects or themes that you can always return to in your writing. To test this, pick any one of your listed obsession and, using language from answers to the following questions, write a poem.

- How were you first introduced to this obsession?

- How does this obsession make you feel?

- What form does this obsession take? What does it look like? Sound like? etc.

- How does your mother feel about this obsession? Your father? A loved one?

- Is it right that you have this obsession? Should you feel proud? Ashamed?

- What in the world would you destroy in order to keep your obsession?Would you destroy anything in the world to keep your obsession?

- How would you describe this obsession and its importance to you to someone who doesn’t share your language?

Rickey Laurentiis Online

Buy Boy with Thorn by Rickey Laurentiis

Buy Boy with Thorn by Rickey Laurentiis