“I do feel that the poem ought to be able to exist separately from the artwork that inspired it. The artwork should be like the muse—present and absent at the same time.”

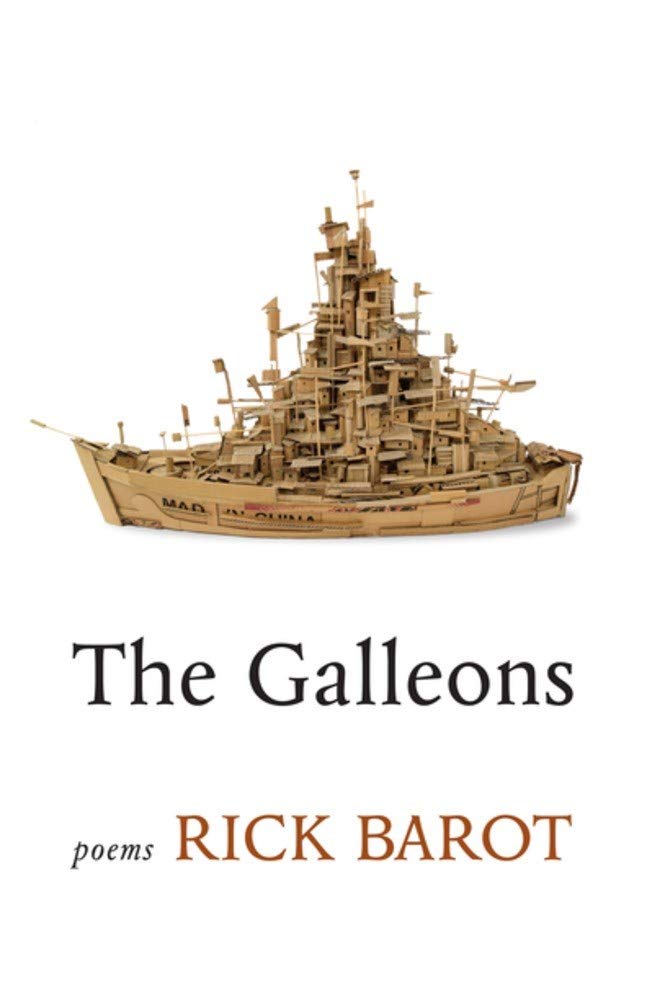

Rick Barot has published three books of poetry with Sarabande Books: The Darker Fall (2002), which received the Kathryn A. Morton Prize; Want (2008), which was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award and won the 2009 Grub Street Book Prize; and Chord (2015), which was a finalist for the LA Times Book Prize and received the 2016 UNT Rilke Prize, the PEN Open Book Award, and the Publishing Triangle’s Thom Gunn Award. His fourth book of poems, The Galleons, was published by Milkweed Editions in 2020. The Galleons was listed on the top ten poetry books for 2020 by the New York Public Library, was a finalist for the Pacific Northwest Book Awards, and was on the longlist for the National Book Award. Also in 2020, his chapbook During the Pandemic was published by Albion Books. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Artist Trust of Washington, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, and Stanford University, where he was a Wallace E. Stegner Fellow and a Jones Lecturer in Poetry. In 2020, Barot received the Shelley Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America. He lives in Tacoma, Washington and teaches at Pacific Lutheran University. He is also the director of The Rainier Writing Workshop, the low-residency MFA in Creative Writing at PLU.

Why bother to engage with another art form in a poem?

Why not? A painting, a photograph, a piece of sculpture—these things have a vivacity that the other things in the world have, and we can interact with them the way we do with those things. So why can’t a poem engage with them in the way we engage with everything else? Maybe the skepticism that seems to be lurking in your question is this one: that writing a poem about another work of art is to diminish the complicated experience that the original artwork generates on its own terms. And that’s a legitimate skepticism. But the ekphrastic poem that’s any good is always trying to be its own thing—its own complicated experience. It’s not trying to speak for the artwork, it’s not simply interpreting the artwork, it’s describing the writer’s charged encounter with that artwork.

Do you see an ekphrastic poem as existing separately from the work that inspired it?

When I ask my students to write an ekphrastic poem, I always tell them that one test for the poem will be how much the poem’s reader will want to go online and look up the artwork that the poem is ostensibly about. If the poem is doing its job, the reader shouldn’t feel that having to see the painting or photograph or sculpture is the way of completing the experience of the poem. That is, the poem should be enough. And so, yes, I do feel that the poem ought to be able to exist separately from the artwork that inspired it. The artwork should be like the muse—present and absent at the same time.

What qualities do you look for or pay attention to in a work of visual art that you might want to write about? What kind of “looking” is necessary?

As someone who actively seeks out encounters with visual art, I’m never at a loss for art to write about, though it’s probably not an exaggeration to say that I only ever want to write about 1% of the things I see. And what is it about the artwork in that 1% category that provokes me into response? When I think back to the poems I’ve written that were triggered by works of art, I can see that I was moved to respond when the artwork helped to crystallize some question or feeling or insight or idea that I’d been troubled by. The encounter with the artwork was certainly an occasion in itself, but more than that, the artwork helped me to work through something. I don’t mean to suggest that, in some totally self-serving way, we should only look at art as sources of insight about ourselves. Rather, I’m saying that we should pay attention to the things that make us stop, and ask why this piece of art—and not another one—has made us stop.

Can you describe an experience of finding an inroad, a point of identification, in a work of visual art? How did that inroad lead you to write a poem?

A number of years ago I was at the Tate Modern in London and came across Dorothea Tanning’s painting “Some Roses & Their Phantoms.” The painting depicts a table with a white tablecloth and gray and white roses on the table. I stood before the painting for some time, puzzling out what its unsettling elements meant. And then I started thinking about the title, “Some Roses & Their Phantoms,” and what the title seemed to indicate: that something of beauty like a rose can also be the site of phantoms, of dark thoughts and dark feelings. Walking away from the painting, I knew I wanted to write a poem that began with the painting itself, but that would then digress into a meditation about other things. A while later I wrote my poem and shamelessly used Tanning’s title as my title. And true enough, the poem begins with Tanning’s painting but then leaps, over and over, to almost a dozen other things. The first inroad, then, was the painting’s vaguely apocalyptic atmosphere—how the painting seemed to be an anti-still-life still life. And the second inroad was the title, in particular the word “phantoms,” and the troubling connotations that the word generated for the painting.

What role does description play in an ekphrastic poem? How do you balance between giving a reader some sense of the original visual art with the broader agenda of the poem?

The balance between description and what I call “editorializing” can vary wildly in ekphrastic poems, and it’s the poet’s job, through trial and error in poem after poem, to figure out how the proportions work. Sometimes it will be important for the poem to provide as much detailed description as possible, especially if those details are instrumental to the reader’s experience of the poem’s ultimate message. And then there will be times when just a quick descriptive sketch of the artwork is enough, allowing the poet to proceed with the other work that the poem is trying to accomplish. There’s no exact science here. In Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” for example, the balance between description and editorializing seems weighted on the side of description, though it’s worth noting that Rilke’s description is heavily inflected by editorializing. On the other hand, Campbell McGrath’s “Sunset, Route 90, Brewster County, Texas,” a poem that consider to be in the ekphrastic mode, nods to description only in the title itself. The body of the poem is an ecstatic, associative swoon on the properties of light: “Now the light is brass and pewter, alloyed metals solid as amber, allied with water, umber and charnel, lucent as mercury, fugitive silver, chalk-rose and coal-blue, true, full of the skulls and skeletons of moonlight…”

John Hollander writes about a poem’s “ekphrastic agenda”—how it “treats” its original. What would you say are the “ekphrastic agenda” of “Child Holding Potato”?

The agenda of “Child Holding Potato” was to trouble the usual agenda found in ekphrastic poems. Art’s power to console, to provide spiritual and metaphysical deepening, to create pockets of contemplation, to provide aesthetic pleasure—these are the pay-offs that conventionally underwrite the ekphrastic endeavor. But as described in “Child Holding Potato,” I experienced something—my sister’s cancer diagnosis—that art couldn’t make right. As someone who puts a lot of stock in art, it was deeply instructive to come up against the limits of art to console. And worse, it was terrible to realize that art can serve as way of deflecting actual experience. “Child Holding Potato” is a kind of transcription of those lessons.

How did you translate the visual work of Miró to a verbal medium in “Miró’s Notebook”?

There was a period when I was obsessed with the Constellations, the series of 23 paintings Miró created in the early years of World War II, when Miró was itinerant and uncertain about what was ahead for him and for Europe. Given the distressing circumstances, one would expect the Constellations to be dark and melancholy, but in fact—to me, anyway—they’re the opposite of that. The paintings are full of whimsy, romanticism, and surreal exuberance. Many of the paintings are comprised of funky little vignettes—little constellations in a night sky. My original ambition for “Miró’s Notebook” was to write a series of 23 poems, one for each painting—each poem was going to be big and messy, like a Poundian canto. But at that point in my writing life, I didn’t have enough in me to write a poem that could be sustained over many pages. And so I settled for “Miró’s Notebook,” which is like a snow-globe compared to the epic things I originally had in mind.

Can you describe the intersection of the ekphrastic and the personal in “Looking at the Romans”?

A number of years ago there was an exhibit of ancient Roman sculpture from the Louvre at the Seattle Art Museum. In one gallery, arranged in a beautiful and startling way, were a few dozen marble busts of noble men, women, and children. Walking among these busts, I was shocked to see that one man’s face looked uncannily like the face of one of my uncles. The recognition was funny and coldly sobering at the same time. Funny because my uncle—an old Filipino man in present-day America—was about as far away from a Roman nobleman, in time and in status, as you could get. And sobering because the recognition highlighted the idea that among the people in an empire, there are those who are memorialized in marble statuary and there are those who are not. “Looking at the Romans” was a way of registering the collision of wit and horror in my mind. But mostly the poem was just a lot of fun. After that first recognition, I forcibly—and I should also say gleefully—imposed the faces of other relatives on the faces of those marble busts. The poem is engaged in a kind of bitter post-colonial erasure.

Traditionally, ekphrasis denotes a work of verbal art that responds to a piece of visual art—either real or imagined. Must ekphrastic poetry refer only to poems responding to visual art or are poems that respond to music or literature also ekphrastic?

I suppose that if we must adhere to the traditional notion of ekphrasis, the poem would have to be in dialogue with a piece of visual art. But in the same way that our contemporary notion of the sonnet has expanded the form in new ways, so too has our notion of the ekphrastic poem changed to include the other art forms beyond the visual forms. And I don’t think it’s worth anything to police the boundary lines between poetic genres. If you’re writing a poem in response to a piece of music or a work of literature and you’re uncomfortable calling your poem an ekphrastic poem, there’s easily another category you can invoke: the ode.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

When I was an undergraduate, my mentor was the great writer of nonfiction, Annie Dillard. For most of those undergraduate years I wanted badly to be a writer in the vein of Lillian Ross, John McPhee, Susan Orlean, and the other fabled nonfiction writers affiliated with The New Yorker. In Dillard’s classes, she taught texts from all the genres, and the students could write in whatever genre they loved best. In my last year or so of college, in one of those classes, I started being envious of the cool things the poets were writing, and I began to write poems. In my nonfiction, I was always eager to get to the parts where I could use lyrical language. When I started writing poems, I saw that I could arrive at those places of intensity much more quickly, without all the apparatus I’d needed as nonfiction writer: exposition, scenes, characters, and so on. Poetry’s economy felt like a kind of belonging, and by the time I graduated from college I knew it was my genre.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

I think the “writing” part of “creative writing” can be taught, because that part involves craft and technique, which are absolutely teachable and learnable. But can the “creative” part of “creative writing” be taught? I’m not sure. As a teacher, part of my job is to describe to my students the habits of being and attention that can lead to strong writing. I can tell my students about cultivating a work ethic that embraces focus and wildness at the same time. But can creativity—that alchemy made of alertness and dream—be taught? Probably not. Maybe creativity is something you have, or don’t have, from the start.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

There are books of poetry that immerse a reader in poetry as poetry, and there are books about poetry that immerse the reader in poetry’s technical and theoretical dimensions. I’ll list five of each, though it’s worth saying that these lists are good just for today, because if I had to come up with these lists again a week from now, they would probably be comprised of very different things. The first list: Elizabeth Bishop, Collected Poems; Lucille Clifton, Collected Poems; Jorie Graham, Dream of the Unified Field; Wallace Stevens, Collected Poems; Arthur Sze, The Ginkgo Light. The second list: Marianne Boruch, Poetry’s Old Air; Stephen Dobyns, Best Words, Best Order; Anne Carson, Economy of the Unlost; Adrienne Rich, On Lies, Secrets, and Silence; Reginald Shepherd, Orpheus in the Bronx.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

The best piece of writing advice I’ve ever heard wasn’t advice about writing, nor was it even advice. It was this observation by George Balanchine, the choreographer: “There no new steps, only new combinations.” Each person who reads that sentence will probably have a different take on what it means in regards to the practice of art. For me, it’s an invitation to think about what those “new combinations” might mean in my writing, given the essential steps—the essential subjects, the essential ways of seeing and thinking—that I already have in me. As for the advice I give to new writers, it’s this: Don’t clean up your psychic space when you’re first writing your poem. Let everything into the poem, especially the images and gestures and sounds that don’t seem to belong there. It’s probably the case that those unusual things are where the real poem is at.

What are you working on now?

I’m writing poems for a fourth book of poems, tentatively titled The Galleons.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

This prompt goes with the discussion of ekphrastic poetry above. First: think of two pieces of art that you love. This might be a couple of paintings, a painting and a photograph, or a photograph and a piece of classical music. Second: think of a powerful memory. This might be something from childhood, or something more recent—either way, the memory should be of a distinct emotional experience. Third: write a poem that encompasses the things listed above. The aim here is to write a fluidly meditative poem that binds several disparate things together. The challenge will be to find the moves—rhetorical moves, associative moves—that give the poem an inevitable-seeming coherence. For examples, seek out these masterpieces: Larry Levis, “At the Grave of My Guardian Angel: St. Louis Cemetery, New Orleans,” Susan Mitchell, “Leaves That Grow Inward,” Dean Young, “One Story,” and of course Robert Hass, “Meditation at Lagunitas.”