“Poems clarify or surprise, move or excite, perplex or explain. At their best, they deepen our understanding of human life and reconcile us to the terms of human fate. But music… well, music thrills and transports us, leads us to abandon thought in favor of more primal instincts and pleasures.”

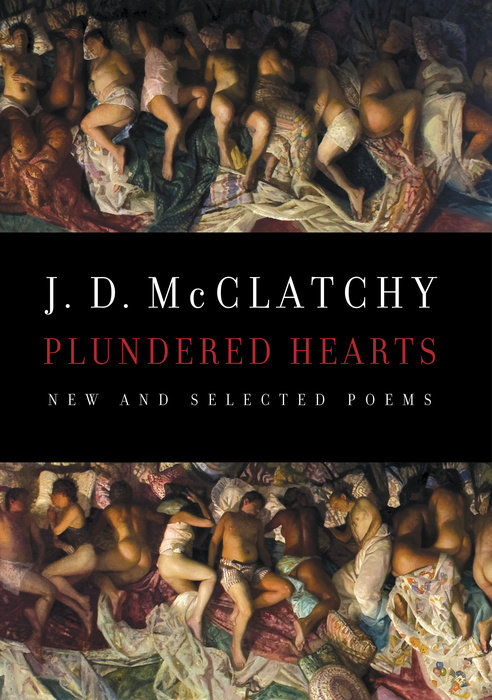

J.D. McClatchy, who died in 2018, was the editor of The Yale Review and the author of many distinguished books of poetry, including Plundered Hearts: New and Selected Poems (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), Mercury Dressing (Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), and Hazmat (Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), which was nominated for the 2003 Pulitzer Prize. He also published three collections of essays: American Writers at Home (Library of America/The Vendome Press, 2004), Twenty Questions (Columbia University Press, 1998), and White Paper (Columbia University Press, 1989); edited over twenty books, including W. S. Merwin: Collected Poems (Library of America, 2013), Thornton Wilder: The Eighth Day, Theophilus North, and Autobiographical Writings (Library of America, 2009), James Merrill’s Selected Poems (Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), and Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Selected Poems (Library of America, 2003); and edited the “Voice of the Poet” audiobook series for Random House. A prominent figure in the world of opera, he wrote opera libretti for such composers as William Schuman, Bruce Saylor, Ned Rorem, Lorin Maazel, Elliot Goldenthal, Tobias Picker, and Michael Dellaira, performed in opera houses around the world.

What is musicality in a poem? How is a poem like a piece of music and how is it not?

Like Caesar’s Gaul, my imaginative life is divided into three parts, I am obsessed with music. I am obsessed with poetry. And I am curious about everything else. (By “everything else,” I’m loosely referring to history, nature, art, sex, the bounty of the kitchen, the psychology of friends and enemies, and other minor pleasures.)

The superiority of music to the other arts is its unmediated immediacy and complete control of the listener’s physical and emotional being. When you read a poem, you can pause where you wish, whether to ponder the implications of a line or turn the coffee machine off. Because a poem is composed a words we use in everyday life—albeit arranged into extraordinary images with their own inner logic—we are dealing with used goods, too often fingered by too many others, ordinary, debased. Music, on the other hand, comes to us magically and immediately. We cannot control it. It possesses us at once and throughout. We surrender ourselves to it. We do not “think” about what is happening or parse it, but merely experience it.

So, at best, poems are only “musical” in an ersatz way. Unlike speech or prose, poems are stylized by patterns of rhythm and (sometimes) rhyme, giving a poem at least the semblance of a piece of music, which depends on repeating motifs and key shifts. The great poets—Shakespeare and Milton, say, or Hopkins–also use diction in a way that estranges it from common use and lifts it to a level of the darting abstraction of music itself.

The “musicality” of poems is crucial. Just “listen” to any poem by Keats or Whitman, Yeats or Merrill. But it remains a secondary force.

Let me give you a tiny example. Here is a quatrain of mine.

The day he left, he said I knew the reason.

Look at the trees. Love only lasts a season.

For years since then I’ve stared at them and seen

Only their blackened branches beneath the green.

The rhymes are blatant. The iambic pentameter is fairly consistent. You can hear the poem move as well as read it. But the point of the poem is not its patterning. Its simple elegance is in service to something besides itself. The poem makes its point, instead, by the rhetorical balance of then-and-now or once-and-since. It takes an image (the seasonal cycle of trees leafing and shedding) and turns it into an image of emotional state of helpless regret.

Poems clarify or surprise, move or excite, perplex or explain. At their best, they deepen our understanding of human life and reconcile us to the terms of human fate. But music . . . well, music thrills and transports us, leads us to abandon thought in favor of more primal instincts and pleasures.

How do the forms of music influence your poems?

Long before I read that Whitman claimed for his poems the direct influence of the floating, swooping lines of bel canto opera, performances of which he attended regularly in New York, I thought I was doing the same thing in my own work. Maria Callas—everything she sang!—was my muse: dramatic, intense, abrupt, writhing. Looking back now, that idea was a fantasy. My poems were what they were, and I probably wrote many of them while listening to Callas . . . or Mahler or Rachmaninoff or Elgar, anything with a long, aching arc. Only later did I realize that, all along, it was actually the forms of poetry itself that influenced my work. Milton, Pope, Yeats, Auden, Merrill, the Australian Stephen Edgar—these were and remain poets whom I study: the structure and weight of their lines, the stanza shapes and darting rhymes, the way an argument is advanced. Many of my American contemporaries I greedily, gratefully read the same way: James Richardson, Louise Glück, Chase Twichell, Kay Ryan, Robert Pinsky, Carl Phillips…oh, and so many others. And nowadays, the only time I don’t have music on in the background is when I am drafting a poem.

You’ve written and translated many libretti for opera. How is writing a text for singing different from writing a poem?

Night and day. A poem wants to pack as much into itself as possible—encoded imagery, leaping lines and stanza-breaks, a congeries of voices, buried emotions, all manner of allusions and implications. A song text or an opera libretto wants none of that.

My job as a librettist is, first of all, to write something that the composer wants to set, that elicits music from him. Those words can be beautiful or banal, but they have to draw music out of him. I learned at the beginning of my career that if the composer is uninspired by what I’ve written, I don’t argue with him or explain its intricacies. It has failed, and I try something else. Second, my job is to create musical possibilities for the composer, so I try to think musically.

Also, my job is finally to make the singer look good on stage—vocally and dramatically. That means, first, thinking about vowels and consonants. In the play “Our Town,” for instance, Emily wants to revisit her twelfth birthday. Twelfth is too difficult to sing, so I changed it to her thirteenth birthday. There are constant similar adjustments. And the words have to be heard and understood when sung over a huge loud orchestra, and projected to thousands of drowsy audience members who rise tier upon tier.

A poem generally we read to ourselves. We bask in the light that splinters in its prism. We read and digest at our own pace. The best poems have their music in them already. Setting a great poem to music, as someone has said, is like looking at the light through a stained-glass window.

How can poetry be a space for creating understanding about the work of medicine and about the experience of being a doctor or a patient?

I am not entirely sure it can. Poetry allows us a chance to interact with the human imagination in all of its range and surprise. To be a good physician, one should be able to interact with human beings, people, not just their disease. So, poetry and Literature in general can be good things for doctors, but they are good things for everyone really. They allow us the chance to walk in someone else’s shoes. They show us the wide range of what it is to be human and not just what it takes to be ourselves.

Could you describe the process of writing the aria, “Dearest Mother and Father…” from Emmeline?

There was a similar letter in the original novel, Judith Rossner’s Emmeline. I had changed the language of the whole opera to give it a Biblical wash, as it were. The idiom of characters gives us a sense of period and location, and of course I’d meant it as well to reflect the harsh Puritanical sensibility of the community. So Emmeline’s religious asides were added.

The letter is really just the recitative leading to her aria that begins “He’s out there almost every night.” When she reads the letter out and is about to sign (and sing) her own name, the seductive Maguire sings it outside her window, as if literally taking the word out of her own mouth. And that starts both her and the aria. There is no such scene in the novel. There is a moment in the novel when Emmeline stands outside Maguire’s house at night to spy on him. That gave me the hint to reverse and compress the situation. The language is some of the most poetic in the libretto, as she sings to this unseen, mysterious figure in the dark, calling her:

He’s there almost every night.

His voice almost sounds like the night,

The night out there

Like a great machine,

Weaving the dark, near to far,

Grinding the day into stars.

He’s there most every night.

He’s out there in the dark,

Like a light, like a fire,

There in the dark.

How can I answer the dark?

Why am I not afraid?

It’s easier just to obey.

What am I to answer?

What does he want me to say?

An aria is usually an inner-directed meditation by a character on the tumult of events that have so far transpired. So that is where the poetry belongs.

Your poem, “My Old Idols,” describes, in one sense, the relationship between several adolescent episodes and music. Do you think music is particularly strong in evoking memory? The poem moves from music (the waltz at the rink) to text (the Latin words in class).

You’ve started more hares than I can jug! Yes, you’re right—the poem moves from music to text, and I hadn’t especially noticed that. But your question is a larger and more complicated one. Of course, music evokes memory. Only think of Proust’s “little phrase.” In a wispy violin melody is discovered a palace of experiences and desires. But how can that phenomenon manifest itself in a poem? Music can accompany memories, but can’t resemble them. “My Old Idols”—all three of its sonnets–has more to do with erotic episodes than with musical. Even listening to Callas sing–for the adolescent me, at least– was an erotic sensation. What stays with us longest, deepest, are physical experiences—the raptures and scars.

Your poem, “Mercury Dressing,” is also a sonnet. What is the particular musical play of the sonnet? Sonnets are often discussed as poems of argument. How does the music of a sonnet advance or complicate a poem’s argument?

Though the very word “sonnet” derives (through the Italian word sonetto, or little sound) from music, I’d favor your word “argument” as the true dynamic of the form. When a sonnet is rhythmically perfect and cleverly rhymes, then indeed one hears its “music,” the sharp turns easily taken. More often, one attends to the sonnet’s confinements, the small arena in which its struggle is enacted. Its hallmark remains its limited freedom, a constraint which dominates the form and is usually the very subject matter embodied in that form as well. If there is music, it is straining to release itself. It echoes vainly around the cell’s walls, growing more refined and eerie. The antiquity and artificiality of the sonnet almost always work in its favor. I wrote “Mercury Dressing” in the subway, coming home from an auction during which I couldn’t bid any higher for a drawing called “Mercury Dressing” by Pavel Tchelichew. I wrote the sonnet, as it were, to compensate for my loss. But then how many millions of poems have been written for precisely that reason?

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

I wrote as a child, intrigued by the sound and play of rhyming words. I showed everything I wrote to my mother, not because I wanted her to love me more but because I wanted her to prefer me to my duller siblings. A shameful motive, but the most authentically artistic one. I continued writing, and even publishing in school magazines, during high school and college—nothing of any interest at all. Then, in graduate school, I took a course in American Poetry from Harold Bloom, and that master upended every shallow assumption I’d had about poetry, and make me realize how high the stakes are for anyone wanted to write a real poem. I bit my lip, and tried harder. Still, since I had nothing to write about, I thought I could disguise that fact with a shower of glittering language. It took another few decades to realize it wasn’t words that matter, it is truth. What also an a profound effect was meeting poets—Lowell, Bishop, Auden, Merrill, Sexton, Warren, Hollander—poets of all stripes, and all of them inspiring in me a renewed sense of discipline.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

I never took such a course while I was in school, but I have been teaching them for decades now. A workshop can help you make more mistakes faster. If that serves to get them out of your system, so much the better. At least a workshop makes you more self-conscious about what’s you’re trying to do. It forces you to read more carefully the work of the old masters, and to sense how your peers are thinking, or how they write about what they’re thinking. It can teach you a technical prowess and an impatience with trivial emotions. The ideal is that every courses at several levels, beginning with prosody, students improve enough to be surprised by their own work, how far it seems from the ambitions and satisfactions they began with. I always remember John Barth’s witty remark: “Technique in art has about the same value as technique in lovemaking. That is to say, heartfelt ineptitude has its appeal and so does heartless skill, but what you want is passionate virtuosity.” That’s where, if you’re lucky, you’re headed in a creative writing class.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

My shelves are sagging with every kind of reference book, but I suppose you mean books of poetry. There are, of course, reams of British and continental poetry that should be known: Shakespeare, Donne, Pope, Blake, Keats, Browning, Hopkins, Yeats; and Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Montale. And I am omitting, because they are so obvious, so essential, the great classical pillars on which Western literature is built, from Homer to Virgil to Dante. Let me instead just stick to American poets. A serious student should read, study, memorize, and adore the complete works of Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, and Elizabeth Bishop.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

The best advice I’ve received has fallen into two categories. The first was mild encouragement. I first showed my poems to Robert Penn Warren, who had an office in the Yale college where I was living at the time. I simply knocked at his door, and held out a sheaf of poems. But he was patient and kind; he read the poems, asked me to send him more, and invited me to dinner. The second and equally valuable advice I received was precise and stinging criticism of poems I was drafting. I was fortunate enough to have James Merrill as a friend, and when I would send him a poem, it came back with just a few marginal comments, but each one pointed to a horrid flaw I had missed. I never wanted his bland approval, I wanted to sharp eye spotting the rotten spot in the pear.

My own advice to younger writers is to write for the dead, not for an audience of your bland contemporaries. Write a line and then think: what would Keats think of this line, or Millay?

What are you working on now?

Last year I published a Selected Poems, a fairly exhausting chore. It took a year for the muse to re-appear. She’s like that: her appearances are unpredictable. I have learned to take advantage of them, and have written, oh, ten new poems in the past few months. For me, that’s a good clip. But no day goes by without my writing something. I have five new opera projects I am working on. I have essays and reviews overdue. Just as important, I have at Yale a teaching life and an editing life. Other people have wondered how I get so much done. But frankly, I think of myself as lazy.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

I’m not sure I know what “a poetry prompt” is, but if you mean a sort of exercise, here is one. Find an intriguing poem of about twenty lines in length. Slightly abstract or goofy poems—like those of Lowell or Rich or Ashbery, say—work best. Type it up, triple-spaced. Then, in between the lines write a line of your own, “inspired” by the original line but in no way mimicking it. Off-base is fine. The erase the lines of the original poem, and tighten up the batch of your own lines and change what’s necessary to make a “coherent” stanza. With luck, it won’t sound like anything you would have written. Make that Part One of a poem, and write a Part Two following from or based on the one you “drew from” someone else’s work.