“We write poems to woo those we love (including those we’ll never meet…)”

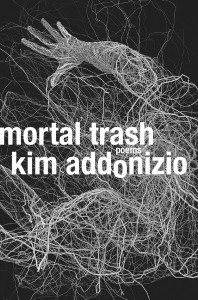

Kim Addonizio was born in Washington, DC. She attended college there and in San Francisco, where she earned a BA and MA from San Francisco State University. She divides her time between Oakland, California and New York City. She is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently My Black Angel: Blues Poems and Portraits, with woodcuts by Charles D. Jones (SFA Press, 2015), and Mortal Trash (W.W. Norton, 2016). Her collection Tell Me was a finalist for the National Book Award. She has also published two novels, two books of stories, an anthology on tattoos, and (with Susan Browne) a word/music CD. A new blues and word CD, My Black Angel, was released in 2015. With Dorianne Laux, she wrote The Poet’s Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry. Her latest book on writing is Ordinary Genius: A Guide for the Poet Within. Wild Nights, a New & Selected from the UK’s Bloodaxe Books, was published in 2015, and a memoir, Bukowski in a Sundress, is due from Viking/Penguin in 2016. Her awards include two NEA fellowships, a Guggenheim fellowship, and two Pushcart Prizes. She teaches private workshops and volunteers for The Hunger Project, a global organization dedicated to empowering people to end their own hunger. Visit her online at www.kimaddonizio.com.

![]() How do you see your amorous and erotic poems fitting into a tradition of love poetry? What resources do you draw on, as influences?

How do you see your amorous and erotic poems fitting into a tradition of love poetry? What resources do you draw on, as influences?

I’m usually not thinking about any tradition when I write. I’m just trying to say something interesting that will surprise me into some awareness I dimly apprehend until I actually get it down. Sometimes I will draw on tradition, though, or play with it. Some of my newer work has been involved with Shakespeare’s sonnets. I flipped the genders, doing a fourteen-poem series in which the first eight enact a woman in love with a younger woman, and the next six her affair with an African-American man. I wanted to see what would happen if the genders were reversed, and the references made contemporary. My editor wanted me to cut them from my most recent book, Mortal Trash. I cut other poems instead. They felt like a new direction.

![]() Do you think the function of the love poem has changed, now that we have more complexly constructed identities surrounding desire?

Do you think the function of the love poem has changed, now that we have more complexly constructed identities surrounding desire?

The content may have changed, given those “complexly constructed identities.” But I don’t think the function has. We write poems to woo those we love (including those we’ll never meet—I’m thinking of Whitman’s poem about the bathers). We write about the ecstatic experience of falling in love and the pain of its failure. Love and desire are core human experiences, however we define ourselves in terms of gender or sexuality. But deviations from the sexual norms of society means that expression of those “deviant” behaviors is going to be fraught in some sense, because those behaviors are marginal. At the same time, those poems can widen the possibilities and create more acceptance.

![]() Is there something native to poetry that makes it particularly or uniquely fertile ground for examining and transforming the experience of desire?

Is there something native to poetry that makes it particularly or uniquely fertile ground for examining and transforming the experience of desire?

All the arts are unique and I’m not sure poetry has any kind of lock on deeper examination or transformation. Certainly because it deals with language, it examines or represents consciousness differently than, say, sculpture.

![]() Do you remember, early on, when you began writing, a breakthrough moment in expressing or confronting something important about love and sex on the page?

Do you remember, early on, when you began writing, a breakthrough moment in expressing or confronting something important about love and sex on the page?

I remember reading Sharon Olds’ first book, Satan Says, as a grad student and being surprised that such things could be said in poetry. I had almost no knowledge about poetry before that. In fiction, I found that kind of liberation in Kathy Acker’s work. Both writers were early influences who let me see there was more territory than I’d realized.

![]() Can you describe the process of writing the poems, “Half-Hearted Sonnet” and “First Poem for You,” which both exploit the sonnet form? What does the sonnet mean to your poetry?

Can you describe the process of writing the poems, “Half-Hearted Sonnet” and “First Poem for You,” which both exploit the sonnet form? What does the sonnet mean to your poetry?

I started as a free-verse poet. In grad school I took a course on meter and form, and for a while became obsessive about sonnets. I literally thought in iambic pentameter for an entire summer. I found—and find—the sonnet to be a really capacious form, despite its small size. Or weirdly, maybe because of it. You have to propose something cogently and quickly, and then there’s that built in turn, or swerve; you can’t just describe something for fourteen lines. There are also the challenges of meter and rhyme, and getting it all to come together and sound natural rather than forced. I’ve done a lot of experimental sonnets, too, where the scaffolding is there but the building looks a bit different.

![]() Do you see one goal of your poems as redefining our cultural sense of female sexuality?

Do you see one goal of your poems as redefining our cultural sense of female sexuality?

I wouldn’t even think of trying to redefine anything. I’m writing what I need to write in the best way I can see to do it. If that contributes to the larger discussion, I’m happy about it.

![]() The tradition of love poetry is rooted in men gazing upon and writing about women’s bodies. How does the poem, “What Women Want,” handle these traditional expectations in the love poem while expressing a female perspective?

The tradition of love poetry is rooted in men gazing upon and writing about women’s bodies. How does the poem, “What Women Want,” handle these traditional expectations in the love poem while expressing a female perspective?

I’ve been surprised that so many people have responded to that piece. I almost didn’t include it in my collection Tell Me. But yes, the Male Gaze and all that. However the poem subverts expectations, or doesn’t, I hope it creates a space for other people to think about women’s bodies and sexual power.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

Poetry led me to it. It appeared in a small attic room in about my twenty-eighth year, beating its iridescent wings as it entered the cauldron of morning, and I followed it to various bookstores where I picked up a few slim volumes based on their covers. The first showed a transparent woman in a forest; hello, Denise Levertov.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

The answer is, of course, yes. And also, no way. You do your best to foster a setting for learning to happen. You expose students to great writing, show them some things about craft, and push them without knocking them down. The rest is up to them.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

I don’t have a required list but can tell you some books that have been important to me, in no particular order:

Letters to a Young Poet, Rilke

The Gift, Lewis Hyde

Collected Poems, Edna St. Vincent Millay

Howl (and Kaddish), Allen Ginsberg

Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

My favorite quote is probably Hemingway’s: that when you write, you have to have a shock-proof shit detector. The advice is simple, and also difficult: do the work.

What are you working on now?

Actually, nothing. I’m just finishing several projects, including a memoir, Bukowski in a Sundress; the new book of poems, Mortal Trash; and a word/music CD, My Black Angel, to accompany a book of blues poems and portraits. I’m waiting for the angel.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

This is one I made up after reading Tony Hoagland’s poem “Dickhead,” about adolescent boys. It ends, “I made a word my friend.” You start out laughing, or maybe being a little offended, and by the end of the piece you’re in a different place with it all. That’s the exercise: to take a charged, loaded word and take us into that word and maybe make us feel differently at the end. Sarah Maclay wrote a poem called “Whore” that does just that. I did “Fuck,” and some of my students wrote poems with titles like “Great Tits,” and “Kike.” The room gets really charged when everyone is tossing out suggestions for titles. It’s a great lesson in how powerful language really is.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- What do you see as the argument of “What Do Women Want?” How does this correspond to your experience of society’s expectations about women?

- Why do you think Addonizio chooses to spend the majority of the poem “First Kiss,” which is written to a beloved, describing a moment with her young child? What kind of effect does this have on you as a reader?

- How does the tattoo function as a metaphor in “First Poem for You”? Do you see the poem’s interest in permanence playing out elsewhere in Kim Addonizio’s work?

- Other than poetry, what genres and traditions are evoked by “Half-Hearted Sonnet”? How does the poem transform those genres, and how do those genres transform the poem?

- Kim Addonizio describes the power of sonnets in her Lightbox interview: “I found—and find—the sonnet to be a really capacious form, despite its small size. Or weirdly, maybe because of it. You have to propose something cogently and quickly, and then there’s that built in turn, or swerve; you can’t just describe something for fourteen lines.” Both “Half-Hearted Sonnet” and “First Poem for You” are sonnets. Compare how these sonnets perform the volta, or “swerve,” of the sonnet.

- There’s a way in which “Beginning With His Body and Ending in a Small Town” draws upon traditional love poetry’s description of the beloved. How do you feel about the juxtaposition of these traditional references with the grittier, more explicit elements in the poem? Are they shocking in the context of this poem, or are they simply more visceral, contemporary, newly beautiful?

In-class Activities

Modern Love

In her interview, Kim Addonizio writes, “I’m usually not thinking about any tradition when I write…Sometimes I will draw on tradition, though, or play with it. Some of my newer work has been involved with Shakespeare’s sonnets.” In this in-class activity, we’ll reflect on the forms and functions of traditional love poetry, and consider how Kim Addonizio’s work “plays” with these structures and ideas.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt:

Love poems in the English tradition often employ strategies such as direct address to the beloved, description of the beloved’s physical features, song-like qualities and refrains, or extended metaphors that involve or implicate the beloved in some way.

To see how poets have used these strategies in the past, you may want to read through some of these classic love poems: “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” by Christopher Marlowe; “Sonnet 130” by Shakespeare; “To His Coy Mistress” by Andrew Marvell; “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time” by Robert Herrick; “The Flea” by John Donne.

Using one of the traditional strategies of love poetry, write a contemporary love poem that draws on your own life and experiences. Give some thought to which traditional strategy would be most useful given what you want to explore about love in your poem.

Kim Addonizio’s Prompt:

This is one I made up after reading Tony Hoagland’s poem “Dickhead,” about adolescent boys. It ends, “I made a word my friend.” You start out laughing, or maybe being a little offended, and by the end of the piece you’re in a different place with it all. That’s the exercise: to take a charged, loaded word and take us into that word and maybe make us feel differently at the end. Sarah Maclay wrote a poem called “Whore” that does just that. I did “Fuck,” and some of my students wrote poems with titles like “Great Tits,” and “Kike.” The room gets really charged when everyone is tossing out suggestions for titles. It’s a great lesson in how powerful language really is.