“Writing poetry has probably been the best teacher for me learning to pray.”

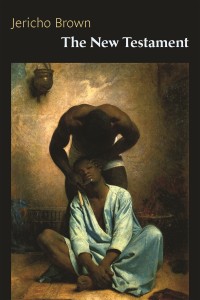

Jericho Brown is the recipient of a Whiting Writers Award and fellowships from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University and the National Endowment for the Arts. His poems have appeared in The New Republic, The New Yorker, and The Best American Poetry. His first book, Please, won the American Book Award, and his second book, The New Testament, won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and the Thom Gunn Award, and it was named one of the best books of the year by Library Journal, Coldfront, and the Academy of American Poets. He is an associate professor in English and creative writing at Emory University in Atlanta.

![]() What is the relationship between poetry and prayer?

What is the relationship between poetry and prayer?

This question has answers that would take me pages and pages to write. I’ll say this much for now: writing poetry has probably been the best teacher for me learning to pray. Poetry asks that I go beyond what I know on the surface into what I did not know I knew within me. With every line, my responsibility as a poet is to come to some greater truth or understanding or realization. Those truths are discovered within myself; I come to them through the music of language and the need for clarity and the connection both of these makes through whatever images the poem includes.

I got better at praying when I figured out that the prayer is not something addressed to someone outside of myself, not even to someone I’d have to beseech for a listening ear. Prayer is much more a process of talking to the me that is within me but is greater than I am. There is someone within us who knows how things work and what should be done and that all is well. When I pray now, I’m praying to the God that is within, the God who is already interested in my well-being and the well-being of the world around me. (This may seem far-fetched, but if we believe God is everywhere, then it’s not so hard to understand that God—all good—is in us.)

The work of prayer and the work of poetry are the same in that they both ask us to broaden our awareness, to become more conscious of that which we’ve avoided or ignored.

![]() Why are poems a space for exploring and challenging spirituality? What is poetry’s relationship to belief?

Why are poems a space for exploring and challenging spirituality? What is poetry’s relationship to belief?

Poems allow us to be faced with the human condition of doubt. At every linebreak is a moment in which we cannot be completely certain of what has happened or what will happen. And then we begin a new line; that beginning is an enactment of faith, of finding out that the world has not been obliterated, that he world has changed to more of what it actually is.

Reading and writing poetry puts us in a position where we must confront that we are beings constantly in motion between doubt and faith.

This is also why people claim not to like poetry. It takes about as much work reading a good poem as it does doing anything else we have to do. Television is much more attractive to those of us who have never been trained in any way whatsoever to face vulnerability and intimacy. By its very nature, poetry asks for vulnerability and intimacy. That’s a kind of work we are taught to avoid at every turn.

![]() You’ve written in your essay in A God in the House, “…when friends invite me to church, I usually find an excuse not to go because I’m afraid that someone behind the pulpit will at any moment attempt to erase or degrade my existence as a gay man. It’s not a comfortable feeling, not a feeling with which to enter a house of worship.” Does this tension between personal faith and contemporary church practice find its way into your poems?

You’ve written in your essay in A God in the House, “…when friends invite me to church, I usually find an excuse not to go because I’m afraid that someone behind the pulpit will at any moment attempt to erase or degrade my existence as a gay man. It’s not a comfortable feeling, not a feeling with which to enter a house of worship.” Does this tension between personal faith and contemporary church practice find its way into your poems?

I think what comes into my poems is a questioning of unnecessary traditions, traditions that harm us much more than they do anything else. For instance, I’m really glad gay people can be legally married, but I hope we do not fall into the trap that leads people to believe that married people are somehow more whole than anyone else. If it plays any part at all, that’s the kind of part the church plays in my poems. I see it as a location of wonder, but also a location where tradition can begin to overstep real spiritual needs.

![]() How do your poems work to incorporate English devotional poetic tradition with the tradition of black Christianity? Do you feel both John Donne and a New Orleans preacher behind these poems?

How do your poems work to incorporate English devotional poetic tradition with the tradition of black Christianity? Do you feel both John Donne and a New Orleans preacher behind these poems?

This is a good question that’s very hard to parse. I don’t know that I can measure how much of me is my academic training or how much of me is my fundamentalist upbringing. As a black poet, it’s a question I think about a great deal, probably because it has no answer. It reminds me of another question I’ve been formulating lately about whiteness and blackness and whether or not I think of whiteness as evil or as something that should simply be checked, the same way we check to not put too much salt in something we cook. Certainly, both of these elements are within me, but should either of them be applauded? Should something of them be dismissed? And why is my relationship to Donne up for question in my mind at all? (I really do think about him a great deal. Certainly, I would not have been able to write my poems if Donne had not existed.)

![]() How do poems ask for things? Does the poem believe in a listener? What if the poem is unanswered? What strategies of entreat do you employ and does that have anything to do with what you ask of your reader?

How do poems ask for things? Does the poem believe in a listener? What if the poem is unanswered? What strategies of entreat do you employ and does that have anything to do with what you ask of your reader?

Well every poem asks us to stop, to pause if only for the time it will take to read it or to see if we will read all of it. The form of poetry, its seeming brevity is one of its tricks. I’m sure poets want to be heard way more than poems do. I’ve noticed that I like talking to the reader as directly as possible in a poem. I hope this makes her feel that she is in the midst of a conversation instead of feeling that she’s in an exam where she must provide the correct answers.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

The library. I’d go through the stacks and read the poems because they were short and because I somehow understood that I didn’t have to know what every part of them meant.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Yes! Teaching creative writing simply means to teach readers to read for the strategies employed by the writers they love most. Once a student can see these strategies, she can employ them in her own work.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

I think that if you read a book by someone who has at least five books and you like the book you read then you should read the rest of that poet’s books.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

“Never say no.” –Nikki Giovanni

“Always use condoms.” –Jericho Brown

What are you working on now?

A play in which Jesus and myself are the main characters.

Can you provide us with a poetry prompt for our students?

Write a poem in the voice of the person to whom you last made love.

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- What is the effect of the device of negation throughout “Prayer of the Backhanded”?

- Describe the syntactic effects of “Prayer of the Backhanded”? How do the sentences work? What effect does that have on you, the reader?

- How does Jericho Brown’s “Romans 12:1” correspond to the biblical passage? How are we meant to understand his poem in relation to the original?

- How does the body function in the poem, “Heart Condition”? How does the poem merge a variety of bodies: erotic, raced, spiritual, physical? How does the poem’s treatment of the body make a statement about the poem’s interest in faith and spirituality?

- What is the “heart condition” of the poem’s title? How are we meant to understand the title’s multiple meanings in the poem?

- How do Jericho Brown’s poems handle tensions around questions of faith and spirituality? How do you think they confront traditional, sanctioned religious belief? You might consider this question in light of Jericho Brown’s essay, “A God in the House…”

In-class Activities

Leap of Faith

In his interview, Jericho Brown writes, “Poems allow us to be faced with the human condition of doubt. At every linebreak is a moment in which we cannot be completely certain of what has happened or what will happen.” In this activity, we’ll experiment with the uncertainty of starting with a line and moving away from it, and the certainty of working towards a line we already know.

Prompts

Lightbox Prompt:

In his interview, Jericho Brown writes, “I got better at praying when I figured out that the prayer is not something addressed to someone outside of myself, not even to someone I’d have to beseech for a listening ear. Prayer is much more a process of talking to the me that is within me but is greater than I am.” For this prompt, write a poem that is a prayer to yourself, to the “you within you but that is greater than you are.” You should address the mysterious, unsolvable, unknowable parts of yourself, the parts of yourself that you ponder, attempt to explore, figure out, that you worry about. The poem can take any form or go in any direction, but the first line and the last line of the poem should be identical. As you write, reflect on how your own personal or spiritual journey in the poem transforms or changes the line with which you began.

Jericho Brown’s Prompt:

Write a poem in the voice of the person to whom you last made love.

[…] Lightbox Poetry is an online resource for students and teachers exploring the place of poetry in the classroom. Jericho Brown is their latest interview: The work of prayer and the work of poetry are the same in that they both ask us to broaden our awareness, to become more conscious of that which we’ve avoided or ignored. […]

[…] A couple months ago, I was alerted to great interviews on Lightbox Poetry with modern day poets, Jericho Brown and Malachi Black. Both artists have strong sentiments around the connection between prayer and […]