“When it comes to the language of the powerful, I have zero qualms in reclaiming maimed language. My goal there is to disrupt and instigate. It is my responsibility to do so, in fact.”

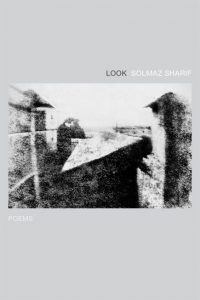

Born in Istanbul to Iranian parents, Solmaz Sharif holds degrees from U.C. Berkeley, where she studied and taught with June Jordan’s Poetry for the People, and New York University. Her work has appeared in The New Republic, Poetry, The Kenyon Review, jubilat, Gulf Coast, Boston Review, Witness, and others. The former managing director of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, her work has been recognized with a “Discovery”/Boston Review Poetry Prize, scholarships from NYU and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, a winter fellowship at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, an NEA fellowship, and a Stegner Fellowship. She has most recently been selected to receive a 2014 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award as well as a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship. She is currently a Jones Lecturer at Stanford University. Her first poetry collection, LOOK, will be published by Graywolf Press in 2016.

![]() What does it mean to be a poet who is documenting instances of language, current events, and other cultural materials? Do you see one of the functions of your poetry as recording some piece of our times?

What does it mean to be a poet who is documenting instances of language, current events, and other cultural materials? Do you see one of the functions of your poetry as recording some piece of our times?

Absolutely. As Nina Simone says: “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” As Forough Farokhzad says: “What’s it to me that no poem in Farsi has used the word ‘explode.’ From morning to night, every direction I look, I see things are exploding.” Poetry is an observational art form for me. It is a quality of attention to the present. It is an attempt at making that present as temporally and spatially large with as few words as possible. It seems that most changes in poetry have come by the addition of vernaculars into the work—a questioning of “why does this not belong in a poem?” Poetry remains alive through a refusal to accept inherited limits of what is and is not worthy of inclusion. Today, as the days before, our language is debased by those in power. This infects our speech and our actions. To not allow in the present would be, for me, a crime.

![]() “Reaching Guantanamo” utilizes such a visual and spatial composition on the page. How do you think about the experience of reading this particular poem out loud?

“Reaching Guantanamo” utilizes such a visual and spatial composition on the page. How do you think about the experience of reading this particular poem out loud?

The poems were inspired by a newspaper article I read about Salim Hamdan, a prisoner at Guantanamo, who, like all prisoners there, received letters from home severely redacted by the Joint Tasks Force. The redactions are silences that come abruptly, unpredictably, illogically and so I read them like that aloud. My voice just drops out. The sole purpose of such censorship is the breaking of the spirit, so I try to read in a way that is halting, painful. “Reaching Guantanamo” is a more theatrical read than other poems of mine.

![]() How do you incorporate other non-poetic material, such as legal documents, the anecdotes of others, government terminology, into your poems? How do your poetics interact with other arts?

How do you incorporate other non-poetic material, such as legal documents, the anecdotes of others, government terminology, into your poems? How do your poetics interact with other arts?

I’m heavily influenced by film. I often say I wish I were a filmmaker, but I’m not very good at playing well with others. Poetry is about as solitary as you can get, so it seems a good fit for me. Our lives are made up of many languages—the language of home, of school, of job interviews, of courtrooms, of the state, of love letters, of advertising. I am not sure I incorporate as much as refuse to exclude them—I’m paraphrasing Muriel Rukeyser here. More and more I am thinking of poetry as a kind of reading rather than a kind of text, so it’s not so much what I do with the non-poetic material as what the reader does with it.

![]() We found audio available for your poem, “Reaching Guantanamo,” which we are linking to with this interview, and you’re also a poet who gives readings. Is there something important about the experience of hearing your poems out loud, attached to a voice? Do you think there is an extra significance to sharing this work with an audience because of its documentary impulse?

We found audio available for your poem, “Reaching Guantanamo,” which we are linking to with this interview, and you’re also a poet who gives readings. Is there something important about the experience of hearing your poems out loud, attached to a voice? Do you think there is an extra significance to sharing this work with an audience because of its documentary impulse?

I hesitate to say “extra” because, on the one hand, it makes the documentary feel superfluous and, on the other, somehow greater than non-documentary poems, whatever those might be. As I understand them, documentary poems stake a social and political claim. Part of their purpose is didactic—that dreaded word. When Muriel Rukeyser writes “The Book of the Dead,” part of the purpose of the poem is to raise awareness of the corporate-criminal, real-time deaths of miners in West Virginia. But I think this is concurrent with the lasting desires of poetry—to speak as the dead, to the dead. But to go back to readings—I think poetry has historically been and still should be respected as an oral medium. The readings are significant not necessarily because they are attached to my voice, but because they can be attached to a voice and made alive again and again. Perhaps more important is the chance to experience the poem with an audience. To be moved as a collective when poems are such private experiences reveals the private/public divide as porous.

![]() How do you decide what it means to treat source materials ethically as an artist? What constitutes “your words”? What do you have ownership over to write about in your poems?

How do you decide what it means to treat source materials ethically as an artist? What constitutes “your words”? What do you have ownership over to write about in your poems?

When it comes to the language of the powerful, I have zero qualms in reclaiming maimed language. My goal there is to disrupt and instigate. It is my responsibility to do so, in fact. When it comes to the “pain of others”—first hand narrative taken from human rights reports, for example—I don’t have a concise answer.

I have an imperfect litmus test for myself. If I am using the words of someone outside of myself (I hardly believe in this division), if I am using source material from an atrocity in a poem, would I be willing to read the poem in front of someone directly affected by that atrocity? In other words, if a Guantanamo inmate were at my reading, would I read “Reaching Guantanamo”? If not, is it because it now rings fraudulent? cruel? pointless? Then I don’t think I have a right to write the poem. Or is it just because I’m scared and don’t want to put my neck out—well, too bad. It’s not about me and it’s not about making sure I do it right. Some of the best I can do for our conversation is fail publicly. Feeling like I would read it in front of the “other” I am writing does not mean I believe I did full justice or that I succeeded in “speaking for” someone. (I abhor “giving voice to the voiceless.” Folks are not voiceless, we are not listening.) Being willing to read that poem despite my discomfort and fear means I know my attempt comes from a place of love. I value this thing: love. The lives of others are not intellectual curiosities or conceptual playthings—they are lives and if I’m not loving them, then I shouldn’t write them.

There is an easy and dangerous gravity that can come from sprinkling a little atrocity into a poem. Put a gun in a poem and see if it doesn’t add heft. Read an autopsy report and see if it isn’t chilling. Callous and fraudulent, this. If the point isn’t to end the evil, then I am not interested in imagining it.

I’m not sure this answers the question though. I guess I don’t aspire to ownership. I don’t find much use in delimiting my words or my authorship. I do believe it’s my duty to name and honor the lives around me; I don’t believe it’s within my authority to do so. I believe the latter, despite its veil of humility and deference, is about ego and self-protection, so I try to ignore it when I can.

![]() In your mind, how is the language you’re interacting with from the Department of Defense Dictionary complicated, transformed, redefined by your treatment?

In your mind, how is the language you’re interacting with from the Department of Defense Dictionary complicated, transformed, redefined by your treatment?

I hope the deadness, the inaccuracy, the deceit of the DoD language is thrown into sharp relief in these poems. I love this string of verbs—complicated, transformed, redefined. I haven’t found the right verb for what it is I am trying to do myself, though it feels like different things in different contexts. In some poems, I want the words to interrupt our daily, oblivious lives. Sometimes, I want to reveal them as maimed. Sometimes I want to juxtapose the word with the actual atrocity it is veiling. Sometimes, to slip into my vernacular with minimal hoopla. Ultimately, I think our ability to name, our desire for language is one of the most terrific (in the old and new sense) powers we have as strange, mortal creatures. The DoD kills not only the bodies but the speaking itself. The poems dissent on both fronts.

In every interview, we ask the following standard questions:

How did you come to poetry?

My mother read me Leaves of Grass. In all honesty, Shel Silverstein is probably the real introduction—he was so thrilling to me and it was the first book I remember exchanging with my mother. It was exciting to think that we were reading the same thing, thinking similar thoughts, our brains lighting up in complimentary ways, without exchanging a word about it. Dickinson, too, my mother gifted me. My mother’s electric typewriter, which made me feel important with each click, so I kept clicking.

Can creative writing be taught? How?

Yes. It is a democratic medium, not a lightning bolt from the gods to the chosen. If creative writing is not picked up, I believe it’s an emotional resistance. There is the craft side of writing, which can easily be taught. I mean, this is the part of writing that can be reduced to work sheets and assignments—strong verbs, concrete details, repetition and rhythm. But there is the other thing, which has to do with just giving a damn. I often cite an anecdote about Thich Nhat Hanh, the Buddhist monk. At a talk, he asked the audience to turn to the person next to them and hug and introduce each other. Routine stuff. They did. Then he asked them to do it again, this time knowing they both will die. That’s the attention and care and urgency creative writing requires— to be willing to see everything shimmering, precarious; to be willing to find the language that lives up to our lives. I don’t think the emphasis is on being creative so much as honoring. It’s not about creating from nothing, but being open to the fleeting awe that is in everything, committing yourself to the seeing behind sight.

What’s your required reading list? Which five books should everyone reading and writing poetry today know?

The Life of Poetry, Muriel Rukeyser

Some of Us Did NOT Die, June Jordan

Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman

The King James Version

Memory for Forgetfulness, Mahmoud Darwish

But ask me again next week and the list will be different.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received or your favorite writing quote? What’s your advice for working young writers?

As for quote: “A poem does invite, it does require. What does it invite? A poem invites you to feel. More than that: it invites you to respond. And better than that: a poem invites a total response.” –Muriel Rukeyser, The Life of Poetry

or more obliquely: “You road I enter upon and look around, I believe you are not all that is here, / I believe that much unseen is also here.”—Walt Whitman, “Song of the Open Road”

or: “Let’s see the very thing and nothing else. / Let’s see it with the hottest fire of sight. / Burn everything not part of it to ash.” –Wallace Stevens, “Credences of Summer”

And advice: “He most honors my style who learns under it to destroy the teacher.”—Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself”

What are you working on now?

Oh, would that I knew.

Can you give us a poetry prompt for our students?

Sharon Olds once gave me this prompt and I like to pass it on: what does it mean to write with the knowledge you were born into?

Classroom Portfolio:

Poems

Discussion Questions

- Discuss the formal patterns of the poem, “Look.” What is repeated in the poem, either word for word or structurally? What do these repetitions evoke for you? How do these repetitions correspond to and advance what you think the poem aims to tell us?

- Discuss the various forms of address within “Look.” To whom is the poem speaking? How do the shifts in address also shift the emotive registers of the poem?

- What role do the gaps in text play in “Reaching Guantanamo”? Why do you think Sharif chose to erase the text of this imagined letter? What information does she erase? How does this affirm or defy your expectations for erasure?

- How does the poem, “Force Visibility,” play with shifting and expanding definitions of words? How does the speaker’s understanding of fascism, for instance, change throughout the poem?

- What is the effect of the brevity of “Vulnerability Study”? How does the poem organize itself in such a short space? How do each of the images describe, or study, vulnerability? Compare the emotional and intellectual effects of this short poem with the emotional and intellectual effects of a longer poem like “Look.”

In-class Activities

Finding Texts

In her debut collection, LOOK, Solmaz Sharif transforms the language U. S. Department of Defense Dictionary to create new political and aesthetic possibilities in her poems. In this in-class activity, students will experiment with generating new poems from found texts and will reflect on what transforming language from different genres and linguistic realms highlights about the material of writing and our individual values as a writer.

Prompts

Let it Matter What we Call a Thing:

Solmaz Sharif’s collection of poems, Look, makes use of words and phrases lifted from the Department of Defense Dictionary to explore the way language holds power over us as citizens. But, according to the book’s description, “Sharif refuses to accept this terminology as given, and instead turns it back on its perpetrators. ‘Let it matter what we call a thing,” she writes. “Let me look at you.’” For this writing prompt, you will create a poem out of a glossary of six words of your choice, with a goal of commenting on, exploring, critiquing, undermining, or somehow transforming the given definitions, contexts, and uses of these words. All six words should come from one particular realm of experience, for instance, from politics, from cooking, from music terminology, from science, from fashion, from whatever you choose. Perhaps some of these examples of jargon will inspire you. Write a poem that strings together these words. You might examine Sharif’s poem, “Look,” as an example. Challenge yourself. Rather than write a poem about the world of the words’ origins and typical uses, try importing them into a new landscape, a new territory of imagery and feeling. See if you can transform these received words, even giving them new definitions and new power, in the context of your own poem.

Writing Prompt (courtesy of Solmaz Sharif:

Sharon Olds once gave me this prompt and I like to pass it on: what does it mean to write with the knowledge you were born into?